On March 19, the Asian Chamber of Commerce and Councilwoman, Jamie Torres, hosted a press conference attended by Asian American Pacific Islander (AAPI) leaders, other community leaders, and Mayor Hancock to make a collective statement of condemnation of Anti-Asian violence. Gil Asakawa was one of the AAPI speakers.

![]()

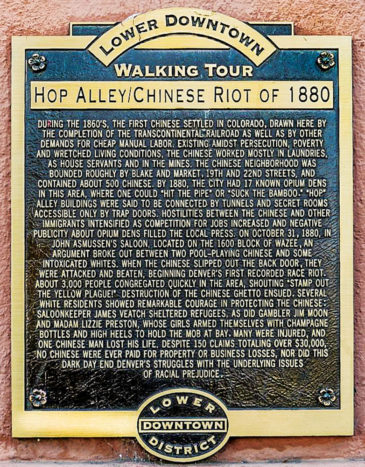

Columnist Gil Asakawa reminds us of the long history of anti-Asian hate as he looks back at the anti-Chinese riot in Denver in 1880. The downtown Denver plaque about the riot is “an example of history written from a white-centered perspective.” Efforts are underway to replace it with a more accurate and appropriate one that celebrates Denver’s historic Chinatown. Photo by Gil Asakawa

Hate crimes against Asians are on the rise. Again. But this time, there’s a difference from last year’s wave of hate: The “mainstream” media, from newspapers to television news, has been reporting on the spike.

Hate crimes against Asians in America are nothing new, and certainly the numbers became noteworthy with the coronavirus pandemic and political leaders like the former president calling it the “China Virus” or “Kung Flu.” The media covered some stories last year, but didn’t fully treat the outbreak of racism as a tragic side-effect of the coronavirus.

The difference now, a year after the pandemic began, is the ferociousness of the attacks, how elderly Asians have been targeted, and the fact that more Asians and Asian Americans are willing to speak out about their experiences. There’s been a year of consciousness-raising and urging our community members to call out incidents. Before, it was difficult to get even young Asian Americans/Pacific Islanders (AAPIs) to report to law enforcement; now it seems like more of us are willing to be on the record with cops and journalists. That’s good.

Amidst this wave of attacks, a group of Asian Americans in Denver calling ourselves the Re-envisioning Denver’s Historic Chinatown Project has been working to remind people that the level of hate against Asians existed even in the earliest days of Asian immigration to this country.

This illustration of Denver’s anti-Chinese race riot on Oct. 31, 1880 was drawn by N.B. Wilkens and published in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, Nov. 20, 1880.

On October 31, 1880, there was an anti-Chinese race riot in Denver that left businesses and residences destroyed in Denver’s now-forgotten Chinatown district. One man, Look Young, was beaten to death and then hanged from a lamppost, and many others were injured. None of the over $50,000 of damage and property was reimbursed.

The riot was sparked by a bar fight in a pool hall between two Chinese men and four white men. The fight poured into the streets and alleys of downtown Denver; within a couple of hours, thousands of white folks stormed through the ethnic enclave—in what’s today called LoDo—busting in windows and chasing the Chinese out.

This race riot was used as an example of why Chinese should no longer be allowed to come to America. In 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, to this day the only law barring immigration to the U.S. by a population’s country of origin. (The legislation remained on the books until 1943.)

But the riot didn’t completely rid Denver of what had been a thriving Chinatown district where Chinese people lived, worked, and established a cultural hub. Even with Chinese immigration closed off, Denver’s early Chinatown was part of Colorado’s ethnic mix into the late 1800s.

By then, the Japanese had been invited as the next wave of cheap immigrant labor from Asia. Like the Chinese (and the Black and Latinx communities), the Japanese settled in certain parts of town because of “redlining” laws that controlled who could live where. The Japanese took over part of what had been Chinatown and then spread out for blocks, where they operated dozens of businesses in the post-WWII years along a stretch of Larimer Street.

By then, the Japanese had been invited as the next wave of cheap immigrant labor from Asia. Like the Chinese (and the Black and Latinx communities), the Japanese settled in certain parts of town because of “redlining” laws that controlled who could live where. The Japanese took over part of what had been Chinatown and then spread out for blocks, where they operated dozens of businesses in the post-WWII years along a stretch of Larimer Street.

A small plaque attached to the wall of a building kitty-corner from Coors Field at the bustling intersection of 20th and Blake Streets is the only reminder of the Chinatown district. The plaque is part of a “Lower Downtown Walking Tour” and is titled “Hop Alley/Chinese Riot of 1880.” It describes the Chinese district of the time, but focuses on the opium dens and the negative “hop alley” reputation. It describes the fight that started the riot and notes that “one Chinese man lost his life” without mentioning his name, but then goes on to name the white people who saved fleeing Chinese by letting them into their businesses, including a whorehouse madam.

I applaud that white people rescued some Chinese, but the description strikes me as a classic example of history written from a white-centered perspective, emphasizing the white saviors over the victims. The title should not focus on “Hop Alley” and should make clear at a glance that it was an anti-Chinese riot.

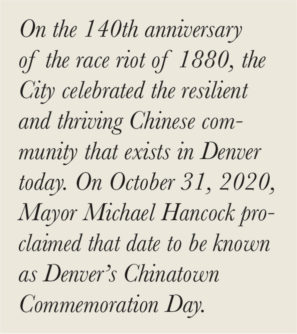

The Denver Asian American Pacific Islander Commission (DAAPIC, of which I was a member until December) agreed to replace this plaque with a more accurate plaque that would commemorate the historic Chinatown district and note the anti-Chinese race riot. I helped draft a proclamation that was made by Denver Mayor Michael B. Hancock last year for the 140th anniversary of the riot on October 31, 2020.

I’m working with a group whose immediate goal is to replace the plaque—we already have some funding from Molson Coors. And we have the support of Lower Downtown Denver’s business organization to find artists to paint a mural (or murals) on the large wall of the building where the plaque is mounted, though we’ll need to raise funds to get all this done.

We also want to eventually place other markers to note Chinatown locations (including where Luck Young was killed), install interactive kiosks to educate people, and, years down the line, open an Asian museum —maybe in the building that had been a Chinese community center! We also hope to launch annual Lunar New Year celebrations in the district. Eventually, we hope some Asian-owned businesses will return to LoDo. As buildings are vacated, wouldn’t it be cool to have some Asian restaurants and shops?

This is a long-term project. Nothing will change overnight, except hopefully the plaque. But it’s heartening to be involved in a project like this that reflects and remembers the hardships that Asians faced a century and a half ago, and to use that memory as one remedy for fighting the hatred that we still face today.

Gil Asakawa is a journalist, cultural consultant, and speaker. He has written “Being Japanese American” (Stone Bridge Press, second edition 2014) and is working on “Tabemasho! Let’s Eat!” a history of Japanese food in America, for 2022 publication. He blogs at www.nikkeiview.com

0 Comments