Former mayors John Hickenlooper (left) and Wellington Webb (right) hold the Stapleton Development Plan with Sam Gary in a photo taken for an April 2010 Front Porch article on Central Park’s 10th Anniversary. Many think of Sam Gary as “the father of Central Park (Stapleton),” but his impact extends far beyond Northeast Denver. He died on Nov. 16.

When people talk about Sam Gary, humility looms large in the conversation. All who worked with him knew his philosophy: “Lead from the back of the conga line.” For Sam, that meant, “As long as the idea you believe in is getting done, you don’t care who gets credit,” says Mike Johnston, the CEO of Sam’s philanthropic organization, Gary Community Investments. (Editor’s note: We’re breaking with journalistic style and using Sam’s first name, the way everyone knew him.)

“A lot of people with a vision like to go it alone, and a lot of people who are very intent on including everyone don’t always have the urgency to push one big idea forward. Sam was an amazing combination of both. The creation of the Denver Preschool Program, the Colorado Children’s Campaign, the Urban Land Conservancy—these are all big ideas that Sam had. He helped bring people together to start them and then launch and carry them out into the world,” says Johnston. “He’s been the big idea and the center of gravity behind a coalition to accomplish big things, but always from the back of the conga line.”

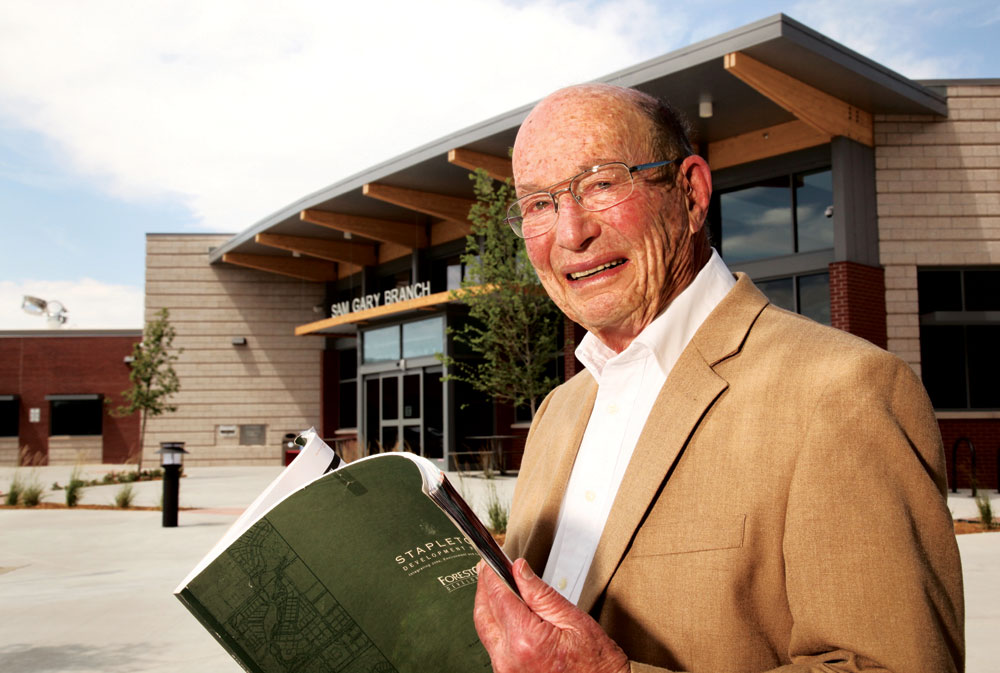

Sam Gary says he didn’t spend much time in libraries as a child because he was always being told “Shhh” and thrown out for being too loud. But after seeing children and parents in Green Valley Ranch’s new library, he said, “…that’s no library. It’s the key to literacy for children, the most incredible thing I’ve ever seen.” He is pictured holding the Green Book (The Stapleton Development Plan) at the Sam Gary Library in Central Park when it opened in August, 2012.

Forty years ago when Dave Younggren was in his 20s, he interviewed with Sam for a job on the financial side of Sam’s oil business—and the job interview turned into a very long conversation about Sam’s business philosophy. “He believed that philanthropy and business go hand in hand, and you can’t have a successful vibrant economy without a successful vibrant society.” Forty years of collaboration as friends and colleagues followed that interview. Younggren says of Sam, “I don’t know anyone with a bigger heart. I know he always felt lucky and he was really driven about other people having opportunities—and that’s true of business as well as in the community. I think there was one thing that always stood out—that he really cared about people. He also had a great sense of humor and he was very humble and self-deprecating.”

Younggren points out another of Sam’s character traits. “You can take a risk and you know somebody will second guess you and say you made some huge mistake. That’s not the way he looked at it. He went into things knowing there were risks involved. We did our homework and made an informed decision and sometimes, you know, the outcome doesn’t work out when you take those kinds of risks.”

“We took anywhere from 10 to 50 percent of the [oil] company profits every year and that’s what supported the foundation,” says Younggren. He says Sam and his wife Nancy were “joined at the hip” in their commitment to the children of Colorado and the work of the foundation.

With the discovery of the very large Bell Creek oil field in Montana (after 22 dry holes), Sam said in a 2012 interview with the Front Porch, “Suddenly this plethora of wealth descended on me. It became very clear to me that it was more money than I needed or could use…So I started giving money away and ended up with a fairly large staff of people—and I really kind of got hooked on that.”

After discovering the oil field, Sam hired an architect to create a land use plan and built Bell Creek Town with homes, a school and a store for the people who operated the 400 wells—and he restored the environment. “If you were to go there today, you’d never know there was an oil field there. It’s beautiful,” he says.

When Sam saw that Denver was going to build a new airport, Tom Gougeon, now President of the Gates Family Foundation says “The opportunity just sort of resonated with him. He had this gut instinct like you can’t just leave this to chance. You have to care what happens [to the old airport land]. He got all the people to come to the table and then that group collectively figured it out.

“He didn’t show up and say, I have the money, I’ll make the plan. He was sort of the piper that got people coming to hear about what’s possible. He was convinced that it could be a model, it could also lift those around it…the quality of the schools…how it would create value and benefits for those people in addition to whatever happened on the site. That’s where it began.

“It was too important to not care about—eventually it’ll work. He was always in that mode. What he did was facilitate the opportunity for people to go figure that out,” says Gougeon, who was the primary author of the Green Book, The Stapleton Development Plan that passed City Council unanimously in 1995. Johnston says, “Sam still had a copy next to his desk every single time I saw him.”

“He was a huge believer in people,” says Gougeon, “so in every one of his efforts, there was some person or a group of people that he just trusted to figure it out—and he would be super supportive of them. He did that over and over and over, and as a result, there’s an amazing alumni of people who have worked on all kinds of things that Sam was behind and made possible.”

0 Comments