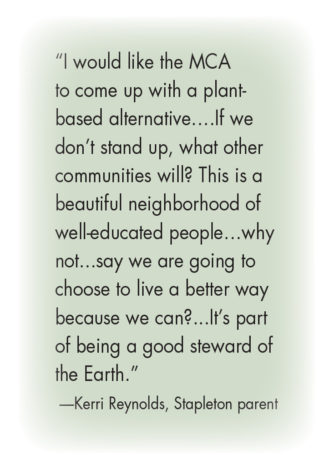

“It was quite the response from the neighborhood,” says Kerri Schoen Reynolds. Her concerned October post about the herbicide Roundup in the “Stapleton Moms” Facebook group garnered about 80 responses within the first 12 hours. Most seemed to share her trepidation about the product, which is widely used in parks managed by the Master Community Association (MCA) and Denver Parks and Recreation. “When you take the kids to the park and you’re seeing these yellow flags and pesticides are being sprayed and you’re walking with your stroller…it’s really frustrating,” says Reynolds, who says the issue has been on her mind “for many years.”

Application Standards

Application Standards

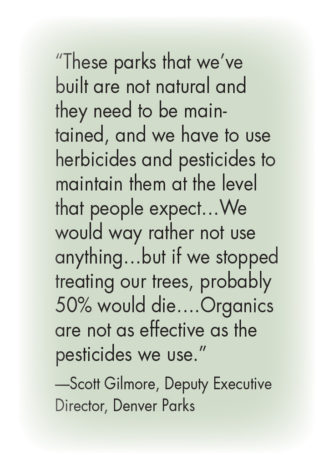

Local and state statutes mandate those yellow flags whenever a professional applies pesticides or herbicides. Denver Parks employees remove their flags after 24 hours, but the public perception may be that the flags indicate an entire lawn area has been treated with Roundup. Denver Parks, MCA, and an expert on weed management at Colorado State University (CSU) all confirm that Roundup is not broadcast sprayed or used on turf. “Usually where we use Roundup is in the sidewalk cracks and in the tree rings….Even if you see the flags, that doesn’t mean we’ve sprayed Roundup. It means we’ve sprayed an herbicide or a pesticide,” says Scott Gilmore, Denver Parks’ Deputy Executive Director.

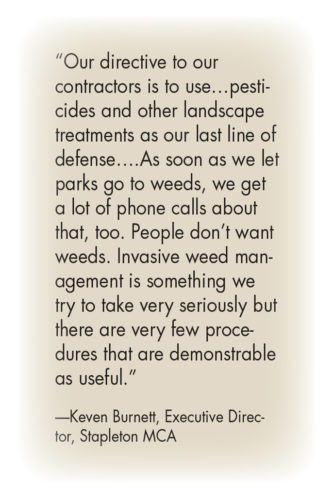

Keven Burnett, Stapleton MCA Executive Director, instructs its subcontractors to minimize the use of pesticides and herbicides and only use them “as a last resort.” The MCA, which manages five sports fields, over 20 pocket parks, and the South and North Greens, does not broadcast spray pesticides or herbicides. Like Denver, it spot sprays as needed and does root injections to treat trees chemically according to Burnett.

An Alternative Approach

The City of Boulder does not use Roundup, concerned not only with glyphosate but also with one of its inactive ingredients— POEA—which would require another story entirely to address.

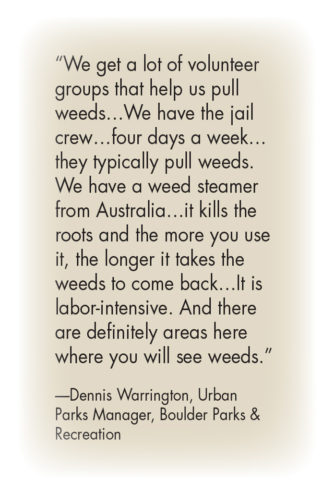

“Park Operations has not used any sprays since 2015…no chemicals whatsoever,” says Dennis Warrington, Urban Parks Manager, Boulder Parks & Recreation. He says in very rare—”almost non-existent”—instances, park managers may use glyphosate on state-listed noxious weeds. Boulder relies on mechanical weed-pulling, using volunteers and jail crews—and admits that weeds will still surface. “We’re not like a lot of other areas where you see the almost perfect bare dirt rings around trees. The only way that that happens is because people spray.”

Warrington says Boulder has also reduced the number of horticulture beds to 275, but still maintains 1800 acres including 380 acres of irrigated turf. Denver maintains 3,000 acres of turf by comparison. Neither Boulder nor Denver treat for dandelions in any way, which is one way both have moved away from pesticides. The two cities allow dandelions to grow for the 2-3 weeks that they appear, mow them down, and reapply grass seed to eventually reduce dandelions. Both Warrington and Gilmore say that they still get calls complaining about the dandelions as soon as the yellow flowers appear.

Gilmore says the City of Denver is one of the largest to have taken the Monarch Pledge and is pursuing certification as a Community Wildlife Habitat by the National Wildlife Federation.

“We don’t want to spray stuff that kills wildlife. We’re trying to minimize impacts,” says Gilmore, who cites the City’s recent adoption of the Game Plan for a Healthy City, a new strategic master plan. The Parks Department is also finalizing new Standard Operating Procedures this year that address how the City uses pesticides in the parks.

A Little Chemistry, A Lot of Debate

Reynolds is not alone in her concerns over RoundUp. With its active ingredient of glyphosate, Roundup has made headlines for years as its health and environmental implications fuel debate across disciplines and international boundaries. A Monsanto chemist first discovered glyphosate’s herbicidal properties in 1970, and by 1974, the company began selling Roundup. Its use really took off in the 1990s, when Monsanto introduced “Roundup Ready” genetically-engineered soybeans, corn, and cotton.

Fast forward to the early 2000s, and what once seemed like the corporation poised to end world hunger had become a bad word in many homes. Monsanto’s business practices gained notoriety with scathing stories in Vanity Fair and elsewhere. Debates over genetically engineered crops, seed contamination, and resistance to glyphosate and other herbicides further tarnished Monsanto’s reputation.

Fast forward to the early 2000s, and what once seemed like the corporation poised to end world hunger had become a bad word in many homes. Monsanto’s business practices gained notoriety with scathing stories in Vanity Fair and elsewhere. Debates over genetically engineered crops, seed contamination, and resistance to glyphosate and other herbicides further tarnished Monsanto’s reputation.

In 2015, the World Health Organization’s International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) determined that glyphosate is “probably carcinogenic to humans,” and found “strong” evidence for glyphosate’s genotoxicity or DNA damage.* In April 2019, however, the EPA released a report stating that it had found “no risks to public health from the current registered uses of glyphosate,” according to EPA Administrator Andrew Wheeler. Confused?

Surely, someone capable of teaching a class called “Molecular Genetics and Evolution of Pesticide Resistance,” would have definitive answers for Front Porch readers. Dr. Todd Gaines, Associate Professor of Molecular Weed Science at CSU has spent much of his career studying glyphosate, particularly plants that have evolved glyphosate resistance. Gaines praises glyphosate’s efficacy on a wide range of weeds and credits it with reducing tillage, which in turn reduces carbon emissions. “There is an environmental benefit to using herbicides that can be overlooked in this debate,” Gaines says, adding that glyphosate helps to reduce “excess nutrients running off from agricultural land,” which causes algae blooms. “The more farmers can use no-till agriculture, the better they protect it from runoff.”

“From an acute toxicity perspective, glyphosate is very safe for people in terms of your short-term exposure to it. You would have to eat more glyphosate than you could possibly fit in your stomach to even have any kind of acute poisoning effect,” says Gaines. He agrees, however, that long-term studies on health and environmental impacts are less conclusive.

“From an acute toxicity perspective, glyphosate is very safe for people in terms of your short-term exposure to it. You would have to eat more glyphosate than you could possibly fit in your stomach to even have any kind of acute poisoning effect,” says Gaines. He agrees, however, that long-term studies on health and environmental impacts are less conclusive.

Full disclosure: CSU’s Weed Research Institute receives funding from a number of companies in the “crop protection industry,” including Bayer, which acquired Monsanto in 2018. “Is there a potential conflict of interest? I’m employed by the state of Colorado, and I’m here to think about the interests of the stakeholders of the state,” says Gaines. “I am looking out for what are the tools they [farmers] have available, what are their problems. I do research on nonchemical weed control,” he adds. “Frankly, there’s overreliance on glyphosate for weed control; it’s been abused in the sense that it just works so well that people got away from diversified weed management.” Gaines says much of his outreach to the agricultural community is to educate them on non-herbicidal approaches to weed management.

Moving Forward

Burnett sees a degree of opportunism in the heightened public concern about glyphosate. He cites “the hundreds and thousands of commercials that run from the legal community that is drumming up business on this subject.” Gilmore echoes this view: “People hate Monsanto…. people are coming after them…” He ascribes consumers’ fears of Roundup in part to the wave of commercials seeking litigants for the nearly 19,000 lawsuits against Bayer in the U.S.

Still, recent studies documenting that glyphosate is bad for insect populations vital for ecosystems, pollination, and the food chain have resulted in staunch challenges for German pharmaceutical giant Bayer at home, too. Germany is phasing out glyphosate use, beginning with city parks and private gardens in 2020. By the end of 2023, glyphosate will be banned entirely in Germany.

Still, recent studies documenting that glyphosate is bad for insect populations vital for ecosystems, pollination, and the food chain have resulted in staunch challenges for German pharmaceutical giant Bayer at home, too. Germany is phasing out glyphosate use, beginning with city parks and private gardens in 2020. By the end of 2023, glyphosate will be banned entirely in Germany.

For Reynolds, the absence of longitudinal studies means that glyphosate remains a concern, and she’s thinking about ways to effect change locally. “People say there is no science that proves it [a glyphosate-cancer link]. Who’s going to trace a person throughout their life and determine at what point is it [cancer] genetic and at what point is it environmental?”

Still, as long as Roundup remains on store shelves, educating consumers—who may not use the product correctly and are not required to place those yellow flags after its application—may be just as important as addressing concerns with the entities that manage our public spaces. Matthew Lopez, Manager, Pesticide Enforcement, Colorado Department of Agriculture observes, “all licensed commercial applicator businesses have demonstrated experience and one of the most rigorous tests across the country to gain that licensure.” He encourages homeowners to consider hiring a commercial applicator if they have concerns about pesticides.

*Note: The IARC’s report was not based on its original research; its working group of 17 experts from 11 countries reviewed about 1000 scientific studies from around the world.

0 Comments