The unassuming manner and quiet voice of Sam Gary belie his success in the rough and tumble world of the oil business. Gary formed the Piton Foundation to share his unexpected good fortune with the community. Among the many causes he has supported was ensuring that Stapleton would be a planned community and would not become urban sprawl.

Editors’ notes are in italics.

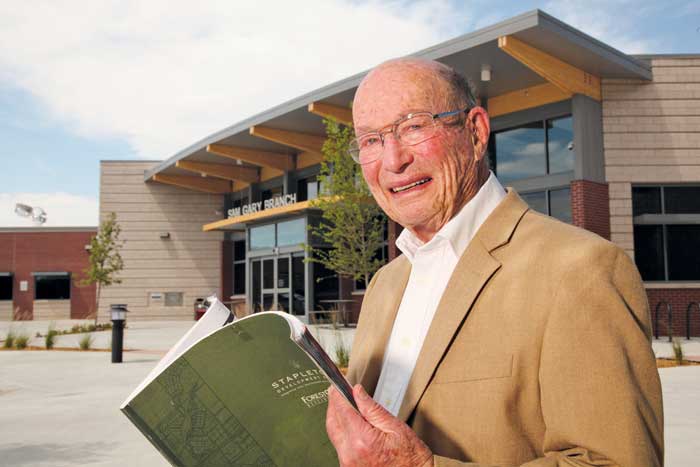

Sam Gary holds a copy of the Stapleton Development Plan (the Green Book) at the new Sam Gary library in August 2012.

Q: You grew up in New York City and were in the Merchant Marine. How did your background shape the person you became?

Sam Gary: I’ve tried to answer that question and came to the conclusion I would call the story “I’ve never done anything on purpose” because it seems like so many of the things I’ve done and places I’ve been were not based on some predetermined sense of, “This is what I ought to do,” and there was probably a lot of what I shouldn’t have done.

Toward the end of World War II, I found myself in Yugoslavia and Italy and other places and saw the population that was left in a defeated country in terrible disrepair…children and families that had nothing. I really hadn’t been exposed to a lot of that. So I couldn’t celebrate (the US winning the war) all the time. It was hard to believe, when you live in a world where everyone is doing OK, and see the devastation when things happen that people don’t have control of. I didn’t start praying or doing anything, it just had an impact on me.

Q: What did you study? Petroleum engineering?

SG: I had a friend from a very early age and he was at Syracuse and he was my favorite fishing partner. They didn’t have anything where you majored in fishing but that was, in part, what brought me there. I wasn’t a very serious student. My major was liberal arts or something. I was not really engaged particularly, but I got through very quickly.

Q: What drew you to Denver and the oil business?

SG: About a year before my time was up (in the Coast Guard), I met my wife and fell in love. She was very young and didn’t know better, so we ended up, much to her parents’ dismay, getting married. I loved to fish and hunt and ski, so we decided to take a look at the bigger world and we drove out to Denver. In the middle of the night we drove down Colfax and stayed in the Fitzsimons Motor Court.

I was interested in looking for oil. It’s kind of like hunting and it seemed like that was something I could do. But I didn’t have very many qualifications. Marvin Davis was also from New York and I got a very menial job over there doing some field work in the land department. I was a scout, actually, and you’d go out and get information. There were hundreds of rigs going in this area, so if someone were successful and you knew about it, there was land you could buy and things you could do. And there were other parts: buying leases, settling damages and dealing with the authorities—so that’s what I did for awhile.

Q: Then you started your own oil exploration company? I heard you had 10 dry holes.

SG: There were 22. Drilling dry holes is not a sin in the oil business and it allowed me to become more involved in different parts of the oil business. I had the feeling there was a very strong need to have a more imposing resume than the one I had. So I decided the thing I really wanted was to go into the best building in town. I had the smallest office there and it didn’t have any windows. It was originally designed as a closet.

In the yellow pages there were millions of independents, but there was a special category there—oil producers. I started putting these deals together and I was pretty fair at it and was getting wells drilled. But I had the same problem—dry holes. I was having pangs of conscience about my name, oil producer, but then I found a small well and decided to keep my business name, Samuel Gary, oil producer.

Leases were much more expensive in Wyoming because there was much more oil in Wyoming and there was hardly any in Montana. Then the industry turned down and I went up to Montana and started drilling just north of the state line. I knew that oil didn’t stop at the state line (although I damn near proved it did) and started drilling these wells. I had been back there and had sworn it off three or four times. But I ended up drilling one more time because a small well I had drilled three miles south of the border was productive. So all my pledges went out the window and I went up and put together another deal. That was one of the wells that discovered Bell Creek, which at that time was the 67th largest in the country and we owned most of it, in large part because I couldn’t sell any more.

Q: How did that change your life?

SG: I became very engaged in getting it drilled up. We retained the operations up there. I’d be damned if I’d turn my operation over to a major oil company. It was a pristine area and I had a strong commitment to not leave it a mess. We had to bring a lot of people in to operate this thing, 400 wells over a wide area and no other resource until a town 45 miles down a dirt road—and not much at the town. I ended up building a little town there. Instead of the typical trailers, I built a school and a store and it had some community activities. (Editors note: Sam Gary worked with an architect to create a land use plan to create a company town with modern buildings for the people there…his first work in community development.)

It was easy because it was a very small community and it was exciting there. One of the interesting things was that, unlike a lot of oil towns where there’s a lot of conflict with the ranchers, this thing worked beautifully. There was a strong sense of community there. I felt a part of it—Bell Creek Town (built in 1967). That field has produced almost 200 million barrels of oil. It’s depleted but with new technology they’re going back in so it’s not through yet. But if you were to go there today, you’d never know there was an oil field there. It’s beautiful.

Q: What led to the Piton Foundation?

SG: We had enough money to get by, but suddenly this plethora of wealth descended on me. It became very clear to me that it was more money than I needed or could use. I thought I should give some of this back somehow. The lawyer said I should start a foundation. So I did—Piton Foundation. They don’t use pitons anymore—they put holes in the rocks. But I decided I wasn’t going to change the name. Pitons help people move up. I thought symbolically that works.

I really was not particularly anxious to take on anything else because I had a lot of stuff. But I think there may be some connection going back to the Coast Guard and seeing that. So I started giving money away and ended up with a fairly large staff of people—and I really kind of got hooked on that. It became not a problem to deal with but something I really became engaged with.

Q: I’ve read your philosophy is you have to drill some dry holes before you discover things that work.

SG: It’s not something you want to say at a petroleum convention. I was pretty good at getting those drilled. Unfortunately, I was not inhibited by my lack of skill, but I was always satisfied that I could get these wells drilled. I’d have some sense of why I thought it was good place to drill—they call it geology today.

I drilled enough wells that people knew me and I got to know a lot of people.

I think Stapleton struck me as being a huge opportunity because I’d lived in New York City and seen urban sprawl in other cities in America. I’m thinking, “There’s this beautiful place and I love it here and here’s the airport.” I saw it simplistically…that if one could somehow wrest it away from the normal processes, it would be a huge opportunity to break the pattern (of urban sprawl). It was simplistic but I found it simplistic enough that I could understand it. So I embarked on this very naïve journey that involved a number of friends who believed there was no such thing as “How?” but it was “Why not?”

If I knew then what I know now, I’d have said, “This is a dumb idea,” but I think there was a relatively small group of people in the political area and the city that you couldn’t deny. Mind you there was no plan…it was an extension of East Colfax.

The City had been responsible for this and time went on and nothing happened and the new airport was being built. By the time the natives were getting restless about what to do with this, we’d sort of gone through the process of that book (most of the writing of the Green Book was done from 1992 to 1995) and we’d raised some money and I had some money and I put it in. It wasn’t an easy sell. (Editors note: Sam Gary was the driving force in getting major businesses, foundations and community leaders in Denver on board to donate and work on a plan for the old Stapleton airport. Four million dollars was raised, $2 million from Gary’s company, Gary Williams, to develop the Green Book.)

In the spring of 1995, I got a call and learned that the plan would become a reality. I went out to Stapleton and the place was packed with press and Mayor Wellington Webb was there. They announced that City Council had just accepted the Green Book without changing one word of the plan for Stapleton.

Q: What was your first reaction when you heard the Stapleton library was named for you?

SG: I’ve not spent a lot of time in libraries (due to childhood memories of being told “Shhh”). I was thrown out of libraries (for being too loud). But what I saw at Green Valley Ranch, that’s no library. It’s the key to literacy for children, the most incredible thing I’ve ever seen. When you go there and you see these kids and you see the dynamic between the parent and the kids, that’s what a library needs to be. (The Sam Gary branch is modeled on the new Green Valley Ranch library.)

My first job after my freshman year at Colo. St. Univ. was to help survey Bell Creek before the houses, store, etc. could be built. The houses, when finished, were beautiful. I went back to Bell Creek about fifteen years ago and the houses still looked beautiful. Sam Gary did a truly unheard of thing building Bell Creek & I am glad he has done so well in life.

My husband grew up in one of those houses and has many good memories.