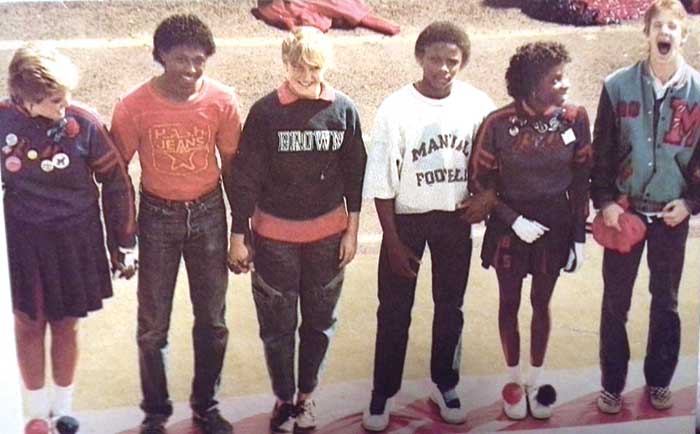

Photo from a Manual alumnus’ Facebook page.

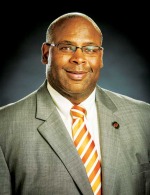

Dr. Jason F. Kirksey, class of 1985, grew up near the Whittier neighborhood and now is associate vice president and chief diversity officer at Oklahoma State University.

Denver Public Schools (DPS) recently released their “Denver Plan 2020,” in which they identify the school district’s primary mission to be developing “Great Schools in Every Neighborhood.” What makes a neighborhood school great? To find answers to this timely question, the Front Porch reached out to students, faculty and parents involved with Manual High School during the busing era.

“It was a transformative experience not just for us, as students, but for parents and for the communities involved,” remembers Jason Kirksey, now Chief Diversity Officer at Oklahoma State University. He describes how his parents, African Americans from Northeast Denver, interacted with Anglo American parents from more affluent neighborhoods, and explains that “my parents would have never interacted with these people under any other scenario. They were from two distinct communities, but they were able to come together for the good of their children and for the good of Manual.”

Alexis McClain, class of 1994, grew up near East High School, and is now the treasurer of the Friends of Manual High School Board and works as an academic advisor at CU Boulder.

The transformative experience Kirksey recalls took place between 1973 and 1995, during which time the Supreme Court ordered DPS to integrate its schools by busing children from Denver’s racially segregated neighborhoods to schools across the city. Manual, located in the Whittier neighborhood, was one of the core city high schools involved in this program. Students from predominantly white neighborhoods were bused into a school that had primarily served the African American and increasingly Latino students within its proximity. Although this social and academic experiment was not without its limitations, those involved with Manual during busing have overwhelmingly positive memories. In fact, the majority of Manual graduates interviewed credit the experience of attending Manual at its most diverse with transforming their lives.

A Tradition of Excellence and Intergenerational Pride

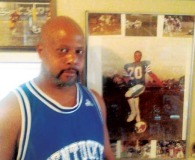

Among the ingredients in what Kirksey refers to as Manual’s “formula for success,” was the school’s well-respected legacy in Northeast Denver. Kirksey’s classmate, Rick Cooper, agrees. Cooper is part of a Manual family that stretches back generations; Cooper attributes Manual’s “huge aura within the community,” in part, to the intergenerational bonds Thunderbolts held.

Though Manual has had its share of struggles in the 20 years since busing ended, the school’s larger history is remarkable. Founded in 1892, Manual is one of Denver’s oldest schools and one of the first schools in the district to educate African Americans. The first African American mayors of both Denver and of Seattle, Wellington Webb and Norman Rice, respectively are Manual graduates. Denver’s current mayor, Michael B. Hancock, is another distinguished alumnus, among a host of politicians, educators, artists and leaders in the business community who can trace their success back to their Thunderbolt roots.

Diversity Brings Resources and a Cultureof High Expectations

Left: Rick Cooper, class of 1985, grew up near the Whittier neighborhood and now works in Denver’s real estate market.

Racial and socioeconomic diversity were also core elements in Manual’s alchemy. According to the National Center for Education statistics, in the year before busing began, DPS was a majority Anglo American school district, in which 66 percent of its students identified as “white,” 14 percent as “black,” and 20 percent were labeled as “Latino”— Asian and Native Americans were lumped into this category as well. However, DPS’s white students were largely isolated in schools that included relatively few students of color. The Supreme Court reasoned in its 1973 Keyes v. Denver School District no. 1 ruling that this educational segregation was not only the result of real estate discrimination and general housing trends, but also the effect of deliberate action taken by the school board to create school boundary zones that separated Denver’s students by race. This separation, as the court had famously ruled in its landmark 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision, was inherently unequal.

Beloved Manual math teacher and football coach Jim Hoops vividly remembers the inequality. Teaching at Smiley Middle School prior to busing, Hoops recalls the building was so “overcrowded we ran double sessions.” There was “no structure to the school; it was like the Wild West.” Inexperienced teachers were assigned to schools with large populations of minority students. These schools were both overcrowded and lacked the resources that the predominantly white schools enjoyed.

Jim Hoops, math teacher and football coach at Manual during busing, has taught at several DPS schools throughout his career and continues to volunteer as a tutor.

Busing attempted to remedy these injustices. Hoops suggests that at Manual the program accomplished this and much more. For many students of color, he recalls, the experience of attending school alongside affluent whites changed their outlook from “will I to college?” to “where will I go to college?” For students like Keith Hammond, whose family was highly educated, the college-bound motivation white students brought to campus did not alter his trajectory much, but for other Manual students who “didn’t know what to ask for and didn’t know what options were out there,” remembers Hammond, the culture of high expectations made a difference.

Diversity Engenders Confidence Through Real World Experiences

Megan Lederer, now a local pediatrician, wrote her college entrance essay about the experience of being bused from a largely white section of Park Hill to Manual; she feels fortunate that she “attended Manual in its heyday; it was held up as this amazing thing for us.” Hoops concurs with Lederer, reasoning that “colleges liked that Manual was a cosmopolitan school,” as evidenced by the large number of white graduates, like Lederer, who went on to prestigious universities.

Beyond impressing admissions counselors, however, Lainie Hodges maintains that her experiences interacting with students from a variety of backgrounds taught her “how to survive in the world.” Jody Hansen agrees. “Bottom line: I learned how to live in the world.” She says with confidence, “I can walk into any job, talk to any person . . . I really learned how to be with people in the world.”

Keith Hammond, class of 1985, lived in the George Washington High School boundary and provided his own transportation to attend Manual. He now lives in Michigan and works as a project manager for an electric company.

All the white Manual alumni interviewed wore their experience at this racially and economically diverse high school as a badge of pride. Tim Tribbett insists: “I love telling people I went to Manual! Sometimes people look at me like I’m crazy,” he laughs. But it’s clear that Tribbett, like Hansen, Hodges and Lederer, views his Thunderbolt affiliation as a signifier that he successfully navigated an unfamiliar environment and graduated with the confidence to engage a diverse world.

School Pride Creates Unity Among Difference

These transformative interactions were nurtured on a campus where the faculty and staff cared deeply about its students and fostered bonding experiences for them. During Manual’s “heyday,” Thunderbolt pride was stimulated through athletic and extracurricular programs like the school’s competitive basketball team and its celebrated choir.

Megan Lederer, class of 1995, was bused from Park Hill and is now a pediatric physician and lives in Lowry.

John Brame, who played on several sports teams, still refers to the campus as the “Bolt House” and he fondly recalls school color days and barbeques. Manual’s integration of very distinct communities, reasons Hammond further, didn’t just have to do with “socioeconomic status and race,” Thunderbolt pride brought together the “jocks, the nerds, and those in ROTC” because it was a school where “the athletes were also involved in drama and in choir . . . it was quite the experience.”

Tim Tribbett, class of 1988, was bused from Park Hill and is now the director of finance at Air Comm Corporation and lives in Stapleton.

The Experiment’s Limitations

For every student like Hammond and Hodges who remember Manual’s mandated diversity sparking meaningful interracial interaction, there are also students like Lorenza Muñoz Scott who suggests that though Manual was “very diverse . . . there was not much interaction between the groups.” Scott’s mother, Sarah McGregor, confesses: “It wasn’t that great of a school for students of color.” She remembers her son, Gerardo Muñoz, entering an Advanced Placement class and the teacher asking him if he was in the wrong place. Kirksey recalls this type of discrimination vividly, “even when students tested well enough to be put into Advanced Placement classes, we weren’t put in there.” While some Manual graduates went on to prestigious colleges and made lifelong friendships across the divides of color and class, other students, in Scott’s words, “fell through the cracks.”

Applying Manual’s Lessons

John Brame, class of 1985, grew up in the Whittier neighborhood and is now a farmer who lives near Manual High School.

Even graduates like Scott who underscore the school’s limitations, nevertheless insists that Manual’s diverse composition “has had a huge impact on my life now . . . and has made me more culturally sensitive.” Alexis McClain credits her “ability to go out and deal with real life situations” to her time at Manual and posits further that students who attend less diverse high schools are “cheated out of” those formative experiences.

Kendrick Lane, who was bused from Crestmoor Park and is now a physician assistant, reminisces: “I feel I gained a broader perspective on life, race and culture at Manual than through any other experience in my life. I feel the experiences I had at Manual, specifically, the interactions with such a diverse student body, served me well in my current line of work seeing and relating to patients from all walks of life.”

Lainie Hodges, class of 1997, was bused from Denver’s Country Club neighborhood and is now chair of the Friends of Manual High School Board and works in professional training.

Jody Hansen, class of 1992, was bused from Park Hill and is now a medical professional.

By 1995, Federal Judge Richard Matsch revoked the court order mandating integration. Siding with opponents of busing, Matsch expressed confidence that the city’s diverse leadership could now fairly divide the district’s public education resources. DPS’s current commitment to establish quality schools in every neighborhood suggests just how much has changed since the days before busing. However, many neighborhoods in Denver remain racially homogenous and, as these Manual alumni bear witness, one of the district’s greatest resources is its diverse population. As testimony from these Thunderbolts suggests, in order for DPS to fulfill its commitment to creating great neighborhood schools, the district must also be proactive in fostering integrated environments.

Maegan Parker Brooks, PhD, is writing a book about the integration of Denver Public Schools.

On the one hand, attending Smiley & Manual during this era of Denver’s intentional racial and socioeconomic integration was a formative experience. On the other hand, I remember so clearly the inner-school segregation that existed, particularly in the AP classes, in the lunchroom, and elsewhere. The article mentions the large number of “white graduates, who went on to prestigious universities” but doesn’t mention the crisis of the shameful achievement gaps that existed between white and African American and Latino students, as evidenced by only 6 black male students receiving diplomas the year after our class graduated. Did integration really benefit all students? Or primarily affluent white students, who had positive, personally enriching experiences and went on to good colleges? I’d love to see, not only some data on graduation and college attendance rates during this era, but more interviews with students from all backgrounds. I’ll be very interested to read your book, Maegan. This topic remains so relevant today.

I’m a graduate of Manual, class of 92. The experience had a very positive impact on my life. It made me realize that racism only exists because people of all backgrounds are not exposed to other cultures. I’m a proud Thunderbolt alum and would not have traded the experience for anything.