From left: The Coconut chair by George C. Mulhauser Jr., named for its shell-like shape that vaguely resembles a fragment of coconut, embodies a relaxed approach to domestic life that was a distinguishing characteristic of midcentury design; the Asterisk wall clock, one in a series of cutting-edge clockfaces designed by Irving Harper in the 1950s and ‘60s; and Harper’s whimsical marshmallow sofa, comprised of 12-inch diameter upholstered discs.

Woman and Man bench for the patio or poolside, by John Risley.

Design in Midcentury America

“Take your pleasure seriously,” was the motto of Charles and Ray Eames, a husband-and-wife midcentury design team.

“Play was essential to their process, as it was to many designers of the time,” said Darrin Alfred, curator of architecture and design at the Denver Art Museum, presenting Serious Play: Design in Midcentury America, through August 25. Featuring 250 works by 40 designers of the postwar era, the exhibition is a romp through some of the most imaginative 1950s and ‘60s home decor, toys and advertising.

From the marshmallow sofa to the ball clock, bold design innovations of the time reflected a changing society, as many families were enjoying more disposable income and leisure time. “It was part of the movement from wartime austerity to a freer time,” said Ann Lambson, interpretive specialist for architecture and design at the DAM.

New materials and manufacturing techniques allowed designers to introduce new looks for home interiors. Visitors are greeted with a display of midcentury modernist furniture pieces, including Irving Harper’s whimsical marshmallow sofa. “I designed it in one weekend,” Harper told Metropolis magazine in 2001. “I made a little model and brought it into the office. It was supposed to be a joke, sort of a game, because I’d never done anything that looked like that.”

Tulip chair with portrait of a girl. The chair’s elegant form contrasts with the freehand quality of its painted decoration.

The exhibition includes textiles and ceramics, as well as films, toys, playground equipment and product design. “Designers were re-imagining and re-invigorating everyday objects,” Alfred said.

A storage and display unit by the Eameses was comprised of modular pieces that could be put together to suit any room. “Consumers were encouraged to make their own expression, to stand out in the crowd,” said Alfred. “It was a response to the Mad Men plain gray suits.”

Irving Harper’s clocks were pieces of sculpture. A wall of Harper clocks includes the ball clock, the kite, the sunflower, the kaleidoscope and the “eye.” “To omit the numbers and have an abstract object that moved on the wall was something no one was doing at the time,” Harper said.

An emerging focus on child development prompted an interest in children’s furniture, including Henry P. Glass’s Swingline toy cabinet that operates on hinges and looks like stacked blocks. Smart toy designs include a city planning set by Gere Kavanaugh, comprised of abstract wooden forms for developing city plans on a child-size scale.

Designers found new and fun ways to brand products, including Paul Rand’s ads for El Producto cigars, in which cigars were brought to life as amusing characters. “Companies of that time challenged designers to surprise the world through imagination and delight,” Alfred said.

Explore this: one of Isamu Naguchi’s play sculptures, intended to stimulate open-ended and creative play.

The large Free Play Zone invites kids to don masks for theater play or construct wooden toys with pieces designed by architect Anne Tyng. Throughout the exhibit, films by the Eameses bring toys and other objects up close. In the film Parade, toys are characters in a narrative about a passing parade. “Their purpose was to draw attention to everyday objects, their beauty and playfulness,” said Alfred.

Left: Charles Eames’ House of Cards, comprised of a picture deck and a pattern deck, with slots to lock them together. Right: The Little Toy, designed to build small theater sets, tents and houses to use with other toys and objects.

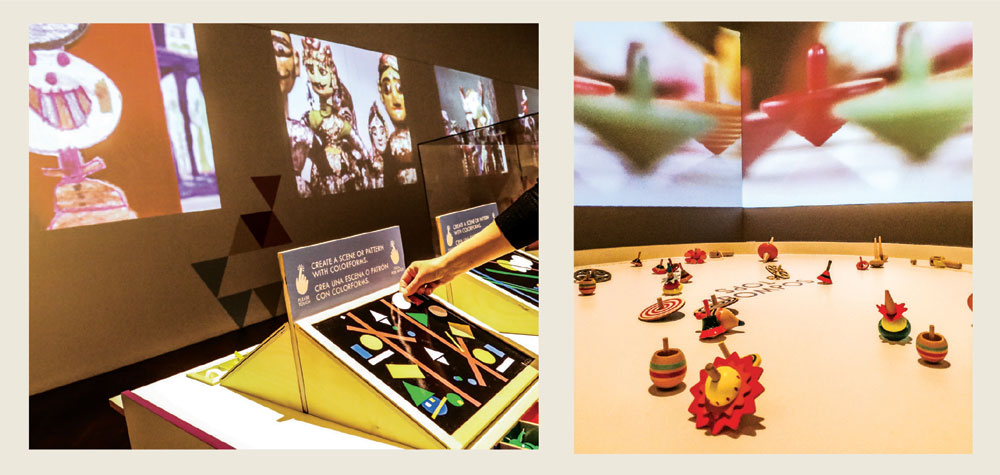

Invitations to Play are throughout the exhibit, including this station (left) where visitors can create a scene or pattern using colored shapes; or spin an assortment of tops (right) on a large tabletop. Charles and Ray Eames’ film, ‘Tops,’ is in the background.

0 Comments