Sherlock Holmes from Stapleton Front Porch on Vimeo.

![]()

Curator James Hagadorn in Sherlock Holmes’ sitting room, where visitors can practice their powers of observation. “The little things are infinitely the most important,” said Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, creator of the Sherlock Holmes character.

![]()

![]()

More than 100 years after Sherlock Holmes solved his first case, the eccentric English detective remains a fascination for audiences of all ages. Why does the character created by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle still impress us with his famous powers of observation and deduction?

“Sherlock Holmes mysteries deliver a sense of the unknown that is compelling,” said James Hagadorn, curator of the International Exhibition of Sherlock Holmes at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science. “Most of us can’t solve the mysteries the first time we read them. With most mysteries we can guess the conclusion, but not with Sherlock Holmes.”

Visitors to the exhibit, open October 23 to January 31, are challenged to solve a crime using methods that were employed by the famous sleuth in his time. “The conclusion—the ‘whodunit’—is surprising; it’s pretty cool,” said Hagadorn.

The exhibition features detailed stage sets, elaborate Victorian-style exhibits and interactive experiment stations that appeal to dedicated Sherlock enthusiasts, the merely curious and families with children who enjoy playing detective.

Museum volunteers observe clues at the crime scene, including a bullet hole and blood stains; pieces of a shattered plaster bust; a smoking seed pod; and parallel markings leading away from the house.

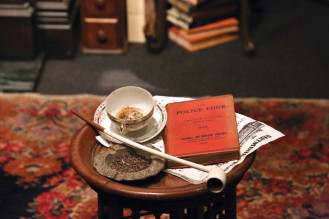

Sherlock Holmes’s sitting room, at 221B Baker Street in London, is recreated complete with a crackling fire, a bearskin rug, a table holding his signature pipe, and a cup of tea. The room gives visitors an opportunity to practice their powers of observation. At first glance, the room’s clutter is almost overwhelming. But on closer inspection, everything shows the hand of a brilliant eccentric.

The next set, a parlor crime scene, contains clues—including bloodstains, a broken bust and a smoking seed pod—for visitors to observe in order to solve the crime.

Physicians investigated evidence found at crime scenes—such as this skull fractured by a bullet and an elbow joint fused by a traumatic injury.

“Through the keen eyes of Sherlock, we learn that seeing is not the same as observing,” said Hagadorn. “Observation at a crime scene is about what is important and what is not; what are its characteristics? A detective can describe it to another detective with their eyes closed and they can visualize the crime scene. When observing, the things that strike you as not normal are relevant. As Holmes would say, ‘the evidence is right in front of us.’ He used that information to reconstruct what happened.”

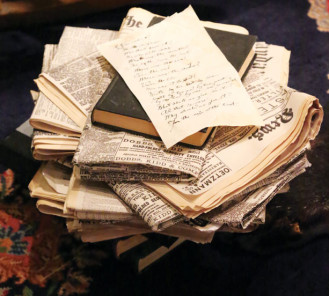

Visitors pick up a “detective’s notebook” to record their observations with stamps and cutouts. They test their evidence with experiments used at the end of the 19th century.

Studying what footprints look like, forward and backward. Holmes reconstructed what he observed at a crime scene to determine what happened.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was a physician who had studied at the University of Edinburgh Medical School from 1876 to 1881. Professors and students in the “surgery arena” were expanding their exploration of anatomy to include investigating how people died. “Forensics didn’t exist yet; they called it ‘medical jurisprudence,’” said Hagadorn. “Conan Doyle himself did experiments on injuries caused by shooting, stabbing and blunt force. Was the cause of death natural or human-induced?

“Doyle was also a huge fan of Edgar Allen Poe, the first writer of detective mysteries. Doyle’s own stories added the scientific method: collecting information, comparing it to a database, using experiments and making an interpretation. No one had done that before. And he made it fun and interesting. He popularized scientific thinking and methodology.”

Historical reenactor Andrew Parker portrays Victorian-era journalist Nathaniel Becker. The experiment reveals the identity of an unknown substance by turning a clear liquid to lavender.

The first Sherlock tale, A Study in Scarlet, was published in 1887. Doyle featured Holmes in four novels and 56 stories, the last published in 1927. Sherlock’s methods of observation, testing and deduction greatly influenced the development of techniques for solving crimes, many of which are still used today.

Holmes’ methods demonstrate the innovations of his time. “The end of the Industrial Revolution was a time of accelerated advances in areas such as communications, transportation and chemistry,” said Hagadorn.

Visitors analyze their crime scene evidence at stations exploring poisonous plants, chemical reactions, ballistics and how to interpret forensic evidence, including the patterns of bloodstains. “All of it is the basis for modern crime scene investigation,” said Hagadorn.

Tickets for the exhibit range from $17.95 for children and students to $23.95 for adults and include admission to the museum. For more information, see www.dmns.org or call 303.370.6000.

0 Comments