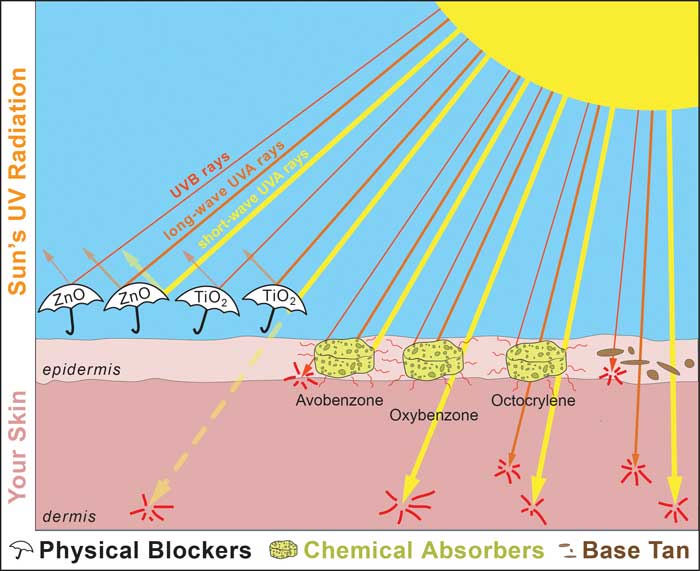

How ultraviolet (UV) rays interact with skin’s melanin granules (i.e. your tan), and suncreen’s active ingredients (i.e. physical blockers & chemical absorbers). This red lines represent heat. Thick red lines indicate skin damage.

As a kid, I remember my first pool party. I also remember lying in a lukewarm bathtub the next day, with 2-inch blisters on my shoulders. If only I’d taken better care of my skin. Skin is our protector—it maintains our temperature and moisture, generates vitamins, and is a sun-warning system. Many of us don’t think much about these aspects of skin—we care how it looks or if it grows cancer.

Thus we slather and spritz sunscreen to keep our skin in good shape. But as we’ve learned with DDT and BPA, some product ingredients, including those in sunscreens, can have side effects that rival the very risks we’re avoiding.

What is it about sunlight that makes us need sunscreen? Sunlight has different rays, including invisible ultraviolet (UV) rays, visible light, and infrared (or heat) light. Most UV rays are a form called UVA. UVA zooms through glass, through clouds, and deep into your skin—it gives you a tan. It wrinkles and prematurely ages skin, facilitates cellular damage and increases the risk of the most serious of skin cancers—melanoma.

A small fraction of UV light is called UVB. These rays penetrate and cause thickening of your skin’s upper layer. UVB radiation helps vitamin D production but also burns skin, damages cellular structures and leads to skin cancers.

Broad-spectrum sunscreens aim to protect us from both UVA and UVB light. They employ “Active Ingredients” that fall into two categories based on how they work: 1) “physical blockers” scatter and absorb UV rays, and 2) “chemical blockers” absorb UV, converting it to heat. Additionally, sunscreens contain inactive ingredients designed to help UV blockers/absorbers stick to your skin, to make them spread easily, and to prevent them from degrading or reacting adversely with one another.

Two physical blockers are commonly used: zinc oxide (ZnO) and titanium dioxide (TiO2). ZnO retards the full range of UVA and UVB rays, whereas TiO2 blocks about a quarter of them. Physical blockers don’t significantly penetrate intact skin to migrate into your blood or internal organs. Toxicology and epidemiology studies of these substances are in their infancy, but thus far little suggests that they’re harmful to humans except when inhaled, such as from household dust or sunscreen sprays.

Chemical absorbers include all the other unpronounceable substances on sunscreen’s “Active Ingredients” list. Each one absorbs a fraction of the UV spectrum—so they’re used in combination with each other to block all the different types of UV rays. For example, avobenzone retards the UVA spectrum but none of the UVB spectrum. It’s often combined with a UVB-absorbing agent, like oxybenzone, to cover the gap in UV radiation reaching your skin. One reason chemical sunscreens have proliferated is because they’re easy to spread, invisible, and aren’t greasy-feeling. Many of these chemical absorbers, including oxybenzone, easily pass through your skin and into blood, organs and breast milk. Of greater concern—some chemical absorbers may behave as endocrine disruptors. Much like bisphenol A (BPA), a compound that was recently removed from clear, hard plastic bottles, these sunscreen ingredients may impact production of hormones such as estrogen or testosterone. This endocrine disruption affects reproductive systems at all scales—from female fetal development to sperm production in grown males.

Although the FDA scrutinizes sunscreen’s effects on skin, most sunscreen ingredients haven’t been tested or regulated for larger-scale human health impacts. Yet there is growing data on their influence. Some starting points for more information are at skincancer.org, ewg.org, and ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed.

In Colorado and for kids, sun is a pivotal part of an outdoor-oriented existence. Sunscreens permit us to cope with UV rays, so we can spend more time outdoors, living in places we’re not genetically equipped to live in, and doing activities that we’re not evolutionarily adapted to. Sunscreen’s rewards come with risks, but sunscreens are getting better and better.

What does my family do? We mitigate risk by making shade and strategizing our sun-time. We hedge our bets by using sunscreens that only contain ZnO or ZnO plus TiO2. We favor ones that apply easily to squirming kids and don’t make us look like Casper the Friendly Ghost. We wear hats outside, and being real pale, I wear a ridiculously huge one. We have fun in the sun, knowing that UV risks come with rewards. And a few wrinkles.

James W. Hagadorn, PhD, is a scientist at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science. Suggestions and comments welcomed at jwhagadorn@dmns.org.

0 Comments