Where did the mountains go? Evening views of Denver the day before and after the Black Forest fire. Camera is ~1 mile southeast of downtown. Images courest of CDPHE.

I used to live in smoggy Los Angeles where on summer days breathing air required a spork. Colorado’s air has been a refreshing respite—until a couple of weeks ago. As I drove home from the mountains, I could barely see downtown Denver. One double-take and a change of radio stations later, it was confirmed—a new forest fire roared to the south.

While this haze was understandable, today I noticed that our air still wasn’t very clear. Are there more forest fires? Or is the “brown cloud” returning to smog our cities? Is our air safe to breathe, or should we be concerned?

Fortunately, unless you’re fighting or fleeing a fire, smoke is an infrequent and nonthreatening risk. For those more than about a mile away, the biggest dangers from inhaling wildfire smoke are getting soot lodged in your lungs or inhaling PAH (polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons). If inhaled regularly and/or in high doses, these nasty compounds can cause cancer, mutations, childhood disorders, or retardation— particularly in fetuses. Sounds scary, but such risks are low because your eyes, nose and throat will give you irritating alarms that you’re breathing too much smoke. If this happens, move to a place where the air is filtered—whether it is your home, a library, or even better, your local brewpub.

Far more concerning and less visible than smoke are the four horsemen of air pollution: fine particles, ground ozone, carbon monoxide and nitrous oxides. These compounds surround and impact us every day.

Fine particles mostly come from engine and power plant exhaust; they are like shrapnel or minuscule time bombs that get lodged in the tiny sacs of your lungs. Ozone is produced near the ground when sun hits your car exhaust, paint vapors and lawnmower fumes; it behaves like bleach or hydrogen peroxide for your lungs. Carbon monoxide mostly comes from tailpipes; it suffocates your red blood cells. Nitrogen oxides mostly come from cars; they act like acid in your lungs and help form the “smog” that you see weekday afternoons.

Fine particles mostly come from engine and power plant exhaust; they are like shrapnel or minuscule time bombs that get lodged in the tiny sacs of your lungs. Ozone is produced near the ground when sun hits your car exhaust, paint vapors and lawnmower fumes; it behaves like bleach or hydrogen peroxide for your lungs. Carbon monoxide mostly comes from tailpipes; it suffocates your red blood cells. Nitrogen oxides mostly come from cars; they act like acid in your lungs and help form the “smog” that you see weekday afternoons.

Together, these compounds act as invisible and visible toxins in the air we breathe. They don’t just affect people who have asthma, bronchitis and emphysema. They affect the active, the sedentary, the old, the young, and even the unborn.

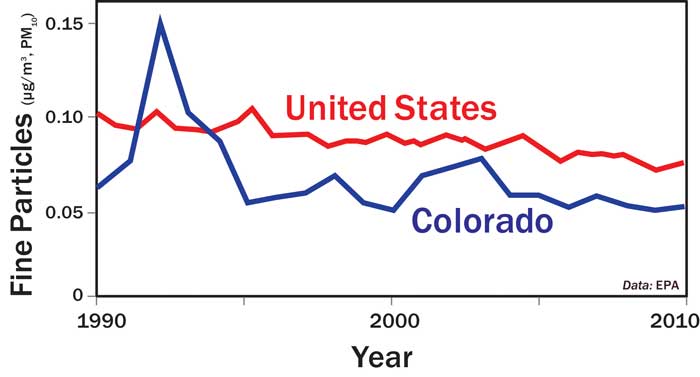

The good news is that we control how much of this stuff is emitted into the air, and Coloradans have done a remarkable job of improving air quality from the days where the Front Range was shrouded in the “brown cloud.” Even given the haze of late, Colorado has better air quality now than it had 10, 20 and even 30 years ago—despite adding more than two million new residents. For example, Colorado’s Front Range cities have, on average, fewer fine particles in their air than most comparable U.S. cities, and levels of ozone and nitrous oxides have annually decreased in lockstep with levels in many formerly smog-shrouded cities in the U.S.

We’ve earned some of these improvements by implementing new technology, such as oxygenated gas and road de-icing agents. In other cases municipalities have fostered cleaner air by expanding vehicle inspections, by restricting wood burning, and by making available more shared transportation.

There is much left to do, and the remaining improvements are up to us. Some changes are as easy as filling up your car at night, not topping off your tank, and postponing that summer painting project until the fall. (I never thought I’d get to invoke “the environment” to procrastinate further on my most overdue house project!)

But the big kahuna of change involves the use of your car, and tips for what you can do are at www.ozone aware.org. If you already have an air-related sensitivity—or think you might encounter one—check out www.colorado. gov/airquality, where you can take the pulse of current conditions and use the air quality forecast to plan your activities. Be sure to look at the AQI (Air Quality Index), a handy metric that synthesizes the effects of all four major air pollutants into one number.

In the meantime, let’s keep on keeping that brown cloud at bay. We all share the air, including the parts we can’t see.

James W. Hagadorn, PhD, is a scientist at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science. Suggestions and comments welcome at jwhagadorn@dmns.org.

0 Comments