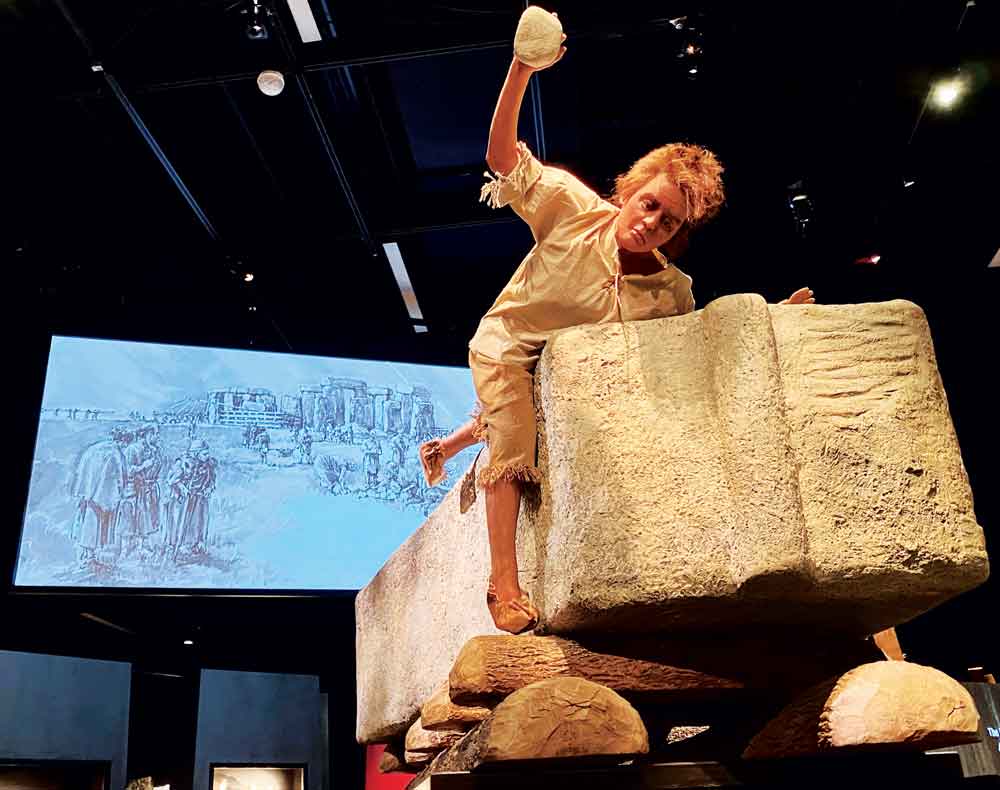

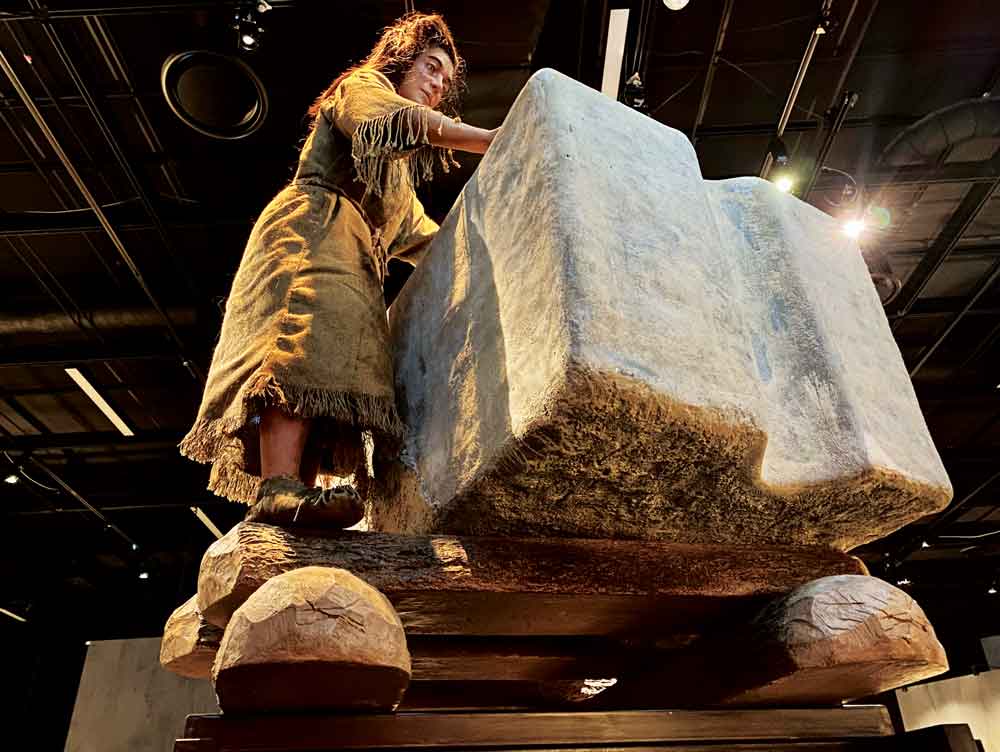

The “Stonehenge” exhibit at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science remains open until September 6. Artifacts, videos, and recreations like this one share the latest insights about this ancient site, which continues to reveal its secrets to archaeologists.

For centuries, people have marveled at a circle of upright stones standing on the Salisbury Plain outside of Wiltshire, England. How did the massive sandstones get there? What purpose did they serve? Who planted them? Spoiler alert: it wasn’t aliens.

Andrew Parker, a DMNS educator performer, explains how Stonehenge changed shape over the centuries, as people moved the now-iconic stones. Stonehenge attracts more than 1.5 million visitors each year.

A UNESCO World Heritage Site, Stonehenge remains one of the most iconic ancient sites, older than the pyramids at Giza or the Mayan temples in Mesoamerica, the site was part of a large network of interconnected ritual sites. Long before ancient people placed the monoliths we associate with Stonehenge, Mesolithic hunter-gatherers camped near the River Avon and erected large posts on the site.

The model in the picture is using an antler pick to dig the circular ditch-and-bank around the stones—the “henge.” (Henges feature a ring-shaped bank and ditch, with the ditch inside the bank.) Stone circles exist throughout Britain and Ireland; Stonehenge’s builders shaped the stones and over time added lintels. Construction required complex social organization to ensure that builders had reliable access to resources.

“It was developed over time from people all across the British Isles,” affirms Andrew Parker, an educator performer with Denver Museum of Nature and Science, which is home to the exhibit “Stonehenge: Ancient Mysteries and Modern Discoveries” through September 6. “As early as 10,000 years ago, it seems to have been a sacred site for hunter-gatherers. At that time, there was probably a lot of game for them to hunt and there are some really interesting physical features of the landscape.”

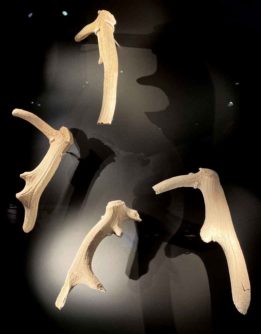

Archaeologists have found antler picks, pictured, as well as bone and stone tools around Stonehenge.

The megaliths we most associate with Stonehenge are of a local sandstone called “sarsen,” which scientists believe came from Marlborough Downs, about 19 miles away moved to the site about 3,000 BCE, these imposing stones endure as silent testament to the ancients’ engineering ingenuity. Scientific advances and ongoing archaeological investigations have brought us closer than ever to understanding who built Stonehenge and associated sites in the vicinity.

Wild cattle and pigs, in addition to deer and other game, drew Mesolithic hunter-gatherers to the area, but ancient peoples also associated the site with the sacred. Cyclical freezing and thawing during the Ice Age had created “parallel gullies and ridges that coincidentally aligned with the summer solstice sunrise and winter solstice sunset,” according the DMNS exhibit.

Far from being an isolated site on the plain, Stonehenge was part of a larger network of cultural and sacred sites. Its construction and shifting design over the centuries reveal the highly complex social organization and planning required for an undertaking on this scale.

These Mesolithic tools dating from 8000-4000 BCE allowed hunter-gatherers to cut wood, dig for roots, cut plants and meat, and scrape animal hides.

Like most cultural sites, Stonehenge evolved and changed over the centuries. The megaliths we see today are not the first human construction on the site, and incoming peoples added and changed the site for centuries. The DMNS exhibit highlights many of these changes, and includes recent discoveries, informed by the archaeologists who continue to research Stonehenge and associated sites. Mike Parker Pearson, Professor of British Later Prehistory at the Institute of Archeology, University College London, has been directing research on Stonehenge since 2003 and curated this exhibit, produced by the Austrian Museums Partner, in collaboration with English Heritage.

In February 2021, Pearson and his team found that the bluestone circle at Stonehenge had previously been installed in a similar sacred circle at Waun Mawn in Wales before being moved to their current location in the Salissbury Plain. Neolithic migrants from Wales dragged these stones on log sleds about 150 miles to bring them to Stonehenge. Each bluestone weighs one to three tons, and it would have taken 50 people over a long period of time through a series of many, small movements to move a single stone to the Salisbury Plain. “These stones may have represented a connection to their ancestral home in Wales,” says Parker.

These are the bones of a man buried with a copper pin, a large dagger and other items around 2400-2200 BCE.

If England is not in your summer travel budget, head to the DMNS to see the original artifacts and learn about the latest research on Stonehenge before the exhibit’s final day on September 6. DMNS is open daily. Tickets for this show are available at www.dmns.org or call DMNS at 303-370-6000.

An engineering feat that continues to amaze, the people who built Stonehenge moved sarsens weighing 4-28 tons each, to the ceremonial site from approximately 19 miles away. They then “locked” the stones together using hammerstones and mauls to create mortise-and-tenon joints. The DMNS exhibit includes many examples of tools, including hammerstones from the site.

Front Porch photos by Steve Larson

0 Comments