Participants at the Sky Dove Balloon Release wrote the names of loved ones lost to violence on their balloons and released them at Village Place Park in Montbello. The event on April 17, sponsored by Families Against Violence Acts (FAVA), was held to honor Denver’s Youth Violence Prevention Week in mid-April.

![]()

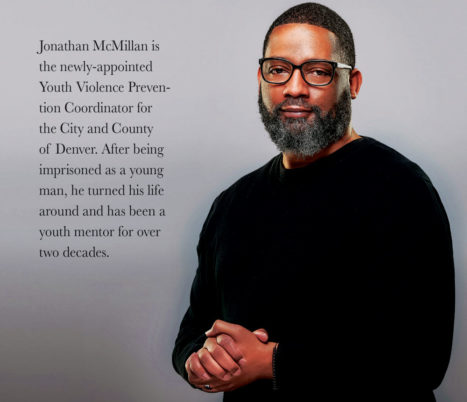

Photo courtesy of Jonathan McMillan

Just three weeks after a mass shooting at a Boulder King Soopers store left 10 people dead, Governor Jared Polis signed two bills into law designed to reduce gun violence: one mandates the safe storage of weapons, the other requires owners to report lost or stolen guns. State Representative Tom Sullivan, whose own son was killed in the Aurora theater shooting 9 years ago, called the new laws “common sense, life-saving pieces of legislation.” And to any who might argue the bills are too small in scope to make much of a difference, he has a quick reply. “Every single step matters. Every incremental step. There isn’t one bill or one pill that will solve it all, but we’re working on it.”

The gun safety advocacy group Moms Demand Action is also cautiously optimistic that some legislative progress is being made. In addition to advocating for state and federal gun legislation, the group works to elect like-minded candidates. Rachel Barnes, a Park Hill mother and elementary school teacher, leads the organization in Denver. “Candidates used to be unwilling to talk about gun safety issues, but that has changed. Jason Crow won on that platform. Tom Sullivan won on that platform. And that has been refreshing to see.”

Linda Colbert, from Families Against Violent Acts, watches as balloons to honor victims of violence float away.

Still, she admits she’s frustrated every time she hears of another mass shooting. “What’s even more troubling is the everyday gun violence—there’s been a dramatic increase in those shootings which disproportionately impact Black and Latino youth. But those don’t get the media attention that the mass shootings do.”

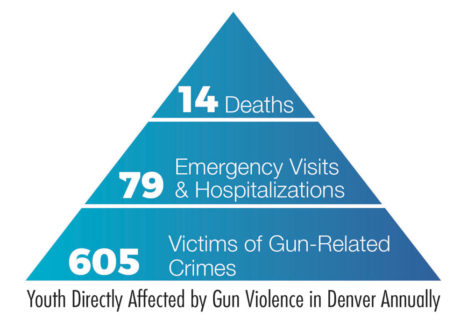

Two years ago, Denver Public Health issued a report that shows an average of 700 young people in Denver under the age of 25 have been directly affected by gun violence each year. Maritza Valenzuela, author of that report, says the findings became a turning point for city officials to create a violence prevention plan that was much more holistic. “Gun violence is a public health problem—and it’s preventable. But treating it as a public health problem—instead of a law enforcement problem—means looking upstream,” says Valenzuela. “Looking at schools and parents, what are the resources that need to be deployed to prevent kids from getting involved with gun violence? How do we support young people instead of trying to put young people away?”

Shortly after the report was released, Mayor Michael Hancock formed the Youth Violence Prevention Action Table (YVPAT) which brought together more than 100 people from city agencies, school and law enforcement groups, along with non-profit organizations that worked directly with gang members and at-risk youth. Jonathan McMillan, who has been working to reduce youth and gang violence for over two decades, has been part of YVPAT from the beginning. Two months ago, he became the city’s full-time youth violence prevention coordinator.

“I’m grateful that Mayor Hancock and other city officials have taken this seriously—allocating a half million dollars to identify risk factors and provide resources to organizations on the ground who are doing the work they do so well but who have been under-resourced.”

“I’m grateful that Mayor Hancock and other city officials have taken this seriously—allocating a half million dollars to identify risk factors and provide resources to organizations on the ground who are doing the work they do so well but who have been under-resourced.”

McMillan knows first-hand the pressures that disadvantaged youth face. Growing up in Park Hill in the 1980s, he says there was a pervasive narrative that Black youth were less likely to graduate high school, more likely to go to prison than college, more likely to die before the age of 25. “It created a paradigm of hopelessness—as though being part of that negativity was what I was supposed to do.”

McMillan says after making some bad choices and ending up in prison, he began to reflect on who he wanted to be. “I committed to reshaping that negative narrative—both on a personal level and a systemic level.”

Aniciea Carey, assisted by Franklin Cruz from the Montbello Organizing Committee, adds a word to a poster of community values created at the Sky Dove Balloon Release event in April.

He became a youth mentor and led gang intervention groups. Four years ago he started Park Hill Strong, a non-profit funded by the Centers for Disease Control dedicated to reducing violence among 10 to 24-year-olds. The group focuses on helping youth develop emotional intelligence: how to handle conflict and communicate in a healthy way. It also tries to make them feel more empowered and connected to their neighborhood. “We helped the kids develop a social media platform to talk about what contributes to violence: mental health issues, economic disenfranchisement, systemic racism. If we address these issues holistically, we’re going to see a reduction in violence in all forms,” says McMillan.

Linda Colbert agrees that too much violence happens because youth aren’t connected to their communities. “So many young people feel isolated, hopeless, so they look for comradery—even if that’s through a gang.” Colbert is part of Families Against Violent Acts (FAVA), which was formed as a grief support group for families impacted by gun violence, but increasingly works on violence prevention. In mid-April, it held an event in Montbello, launching balloons to honor victims of violence. The goal was to bring attention to problems plaguing many neighborhoods in Denver. “The idea is to get people thinking about collaboration, about ways we can get back to community partnerships between families, businesses and even law enforcement. We can’t give up on our ability to bring our community back together to prevent violence.”

Photos for the Front Porch by Christie Gosch

0 Comments