Exhibit at DAM through Jan. 17

Exhibit curator John Lukavic, a Park Hill resident, guides visitors through the Fritz Scholder exhibit at the Denver Museum of Art.

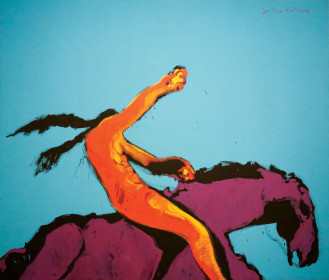

American Portrait with One Eye, 1975.

Park Hill resident and exhibit curator John Lukavic says when Fritz Scholder arrived in Santa Fe in 1964 to teach art, paintings by Native American artists were “flat, representational and often formulaic.” And non-native artists painted overly romantic representations of native people, like works by George Catlin, Frederic Remington and Edward Curtis. Lukavic says Scholder was turned off by this and vowed never to paint an Indian.

In the next few years, however, Scholder’s ideas changed and he thought there was a need for a new way to portray the Indian.

The Denver Art Museum (DAM) exhibit features Scholder’s paintings from 1967 to 1980, and is organized by themes including color, the figure and social issues.

Scholder said color and composition were the two most important factors in his painting, with subject third on his list. Sections of the exhibition focus on: how Scholder challenges sterotypes, native pop, portraiture (which Lukavic says really is a focus on color), dark subjects (morbid and mysterious subjects), and a section on Scholder’s lithographs.

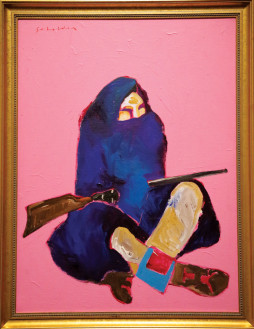

Indian Power, 1972

With The American Portrait with One Eye, Lukavic asks guests to step closer so they are not seeing the whole figure anymore because it’s too big. They’re seeing the color and how the paints are layered on top of each other…how he paired the purple and black and pink and orange and reds.

Lukavic, in the photo above, is shown in the Challenging Stereotypes section of the exhibit. He explains that Scholder, in these paintings, is in dialogue with non-native artists. Scholder takes historic images and makes them contemporary. He was quoted as saying, “I painted the Indian real, not red,” and said his Indians and his cowboys were more real than the traditional artists’ paintings.

In Seated Indian with Rifle, Scholder removes the context that was in the original painting, guarding a captive, and gives it a bright pink background. Now the viewer is free to consider what it may be…opening people’s eyes to the possibilities because they are not being forced to view it in a certain way, says Lukavic.

Indian and Rhinoceros, 1968

Scholder created a seated figure similar in form to the one in The Captive by artist Henry F Farny, but Scholder’s figure does not look like an aggressor.

Scholder created a seated figure similar in form to the one in The Captive by artist Henry F Farny, but Scholder’s figure does not look like an aggressor.

Scholder is trying to get people to recognize that not all the perceptions of native people are accurate and to challenge people to think deeper and open their mind to who native people are.

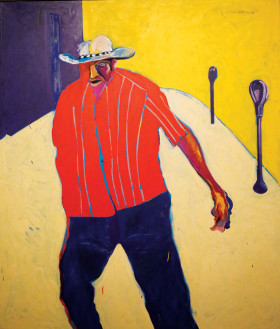

Walking to the Next Bar, left, was a very controversial painting in its time because these are not romantic portrayals of native people. Some criticized Shoulder for highlighting the negative aspects of Indians in America. But to him it wasn’t highlighting the negative. The negative and the positive are all just part of reality. It’s not meant to be looking down on people or making a comment on alcoholism other than that it exists and it needs to be recorded and recognized. If you turn a blind eye to it, you don’t recognize the challenges people face in life, says Lukavic.

Indian Power (top and behind Lukavic’s arm), painted in 1972, had not been seen publicly since 1977, until DAM recently acquired it. “It took me years to find it,” says Lukavic.

Walking to the Next Bar, 1974

“This painting is unique because it is a beacon of empowerment and native pride. Posters of this painting circulated around native communities in the 1970s. It was an incredibly important painting at the time. It’s highly published, but nobody knew where it was.”

How was it found? “It was in a private collection until about 1990. I found an obscure reference to who possibly owned it at that time. Through a lot of tracking down I was able to get in touch with them. They said they had sold it to a family member, but then they stopped responding to messages. Then it showed up at a gallery in Cherry Creek in June. A friend of mine saw it and texted me while I was in New York. “

The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) painting is packed with political symbols, even though Scholder claimed not to paint political themes. The painting seems to associate the BIA, notorious for breaking treaties, with a rhinoceros, which, during the Cold War period of the 1950s through the ‘70s stood for the spread of fascism and communism. Juxtaposed with this is a native man holding a “peace pipe.”

0 Comments