Mike Rex, a best-selling children’s book author who’s penned over 40 children’s books including some adapted to television, used to face a familiar mealtime struggle—his two young boys refused to eat their greens. His oldest son, Declan, declared broccoli “disgusting” and soon a battle over nutrition ensued. Rex, who wanted his son to understand that his thoughts on broccoli were mere opinions—not facts—would tell him he liked broccoli. To which Declan would respond, “You’re wrong. Everyone has to hate it. It’s disgusting.” Rex would counter with, “That’s your opinion.” To which Declan would say, “No it’s a fact.”

The frustrating back and forth—as well as Rex’s young son’s inability to discern fact from opinion—got him thinking the topic might make a good children’s book. The idea percolated for years, and as the idea continued to brew, Rex began to see the topic’s relevance move from the dinner table into the political sphere. Rex says, “I understand that some people are more attracted to facts. That’s why certain students will go towards math and science where everything’s cut and dry and stay away from the liberal arts…but I think there’s been a crossover where people are looking for opinions in science, and I’m like ‘no, it goes the other way.’”

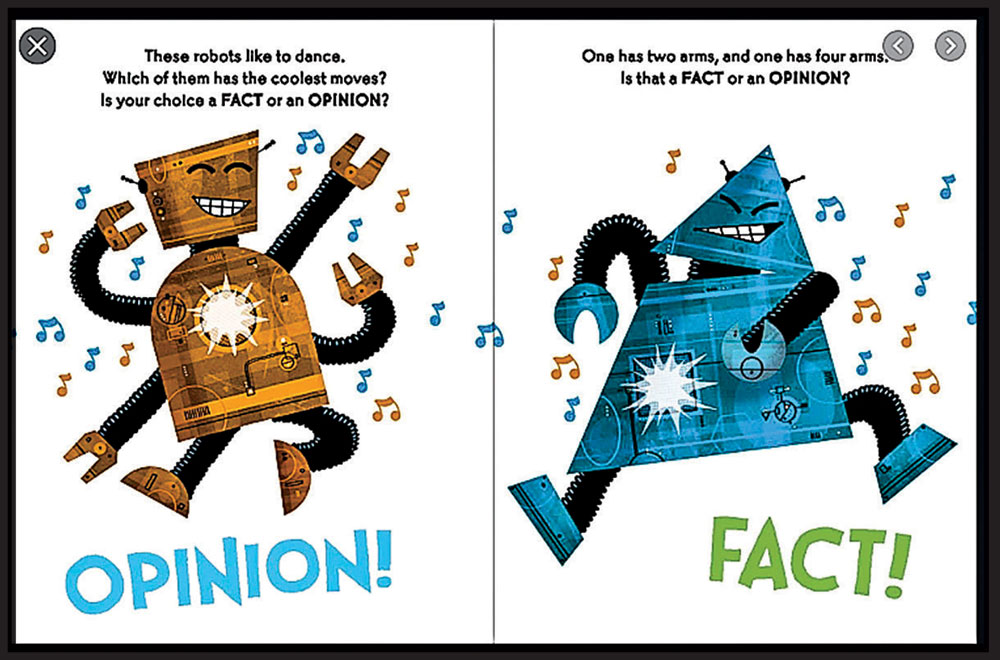

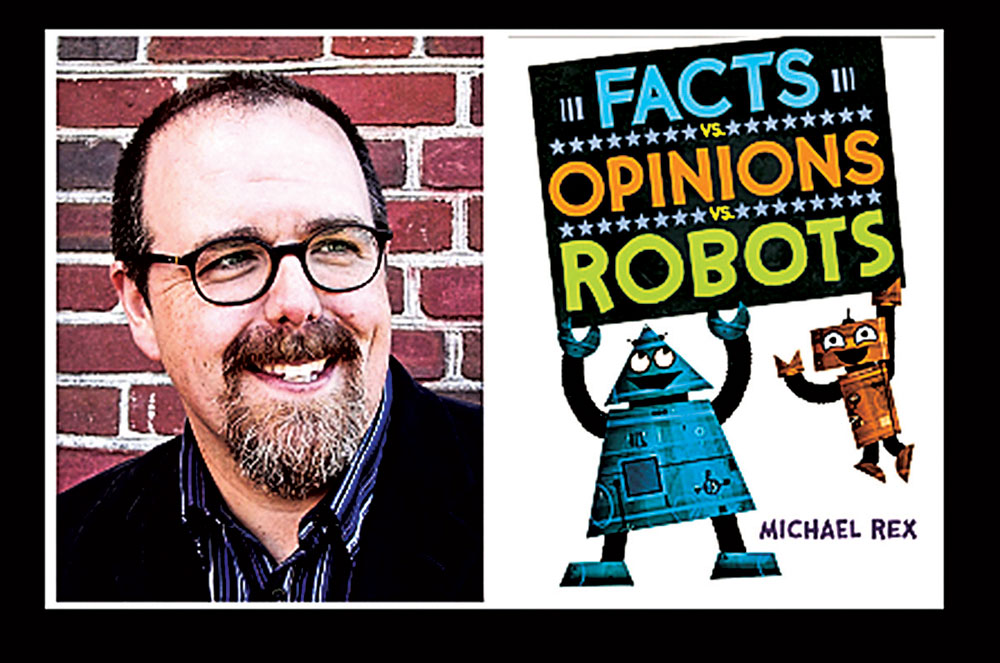

Michael Rex is the author of Facts vs. Opinions vs. Robots. A page from his book is pictured above.

His idea came to fruition in February of 2020 when Nancy Paulsen Books published Facts vs. Opinions vs. Robots. Rex, who also illustrated the book, uses colorful, energetic robots to teach the objective difference between a fact—”Two of these robots have square heads”—and an opinion—”Which robot would you like to be friends with?” Rex said “Sometimes ideas have their moments, and it became the right book at the right time. Editors wanted it right away because of what was going on. Five or ten years ago, it would’ve been a nice book, but it wouldn’t have been as vital an issue; that’s the difference.”

One Amazon reviewer described the book as a reminder, “that it’s nice to listen to one another’s opinions.” But Rex scoffs at that. “That’s not what the book’s about. Yes, we respect opinions as long as those opinions don’t hurt other people. This whole idea [which is taught in school] that every opinion is right and needs to be listened to has gotten people into trouble. At a certain point, you can’t tolerate every opinion. At a certain point, you have to say when facts are present, facts get priority.” He recently tweeted, “One of the points of writing this book was to introduce kids to the idea that sometimes an opinion is wrong (the election was not stolen) and that not all opinions deserve to be heard.”

Other Amazon reviewers seemed to understand what Rex was going for. Rex’s book is described as a “Primer for kids growing up in an era when facts are considered debatable and opinions are oft expressed loudly and without empathy. It’s a welcome use of skill-building to counter an information landscape filled with calls of ‘fake news!’ and toxic online discourse….Perhaps most importantly, Rex’s robots demonstrate that in the absence of enough information, it’s perfectly fine to wait before acting. Vital information for young media consumers; it couldn’t be timelier.” While another called it a “fun, cogent argument for informed and civil conversation.”

So when are children ready for the critical-thinking skills that enable civil conversation? Dr. Jenna Glover, the Director of Psychology Training in the Pediatric Mental Health Institute at Children’s Hospital Colorado, says children as young as five can understand the difference between fact and opinion and at age seven can separate their own experience from others to think critically about varying perspectives.

Rex’s broccoli-haters are in high school now, but he’s still encouraging them to think critically and do their own fact-checking. For more information visit mikerexbooks.blogspot.com.

0 Comments