New book about Denver Mountain Parks is labor of love for Stapleton writer

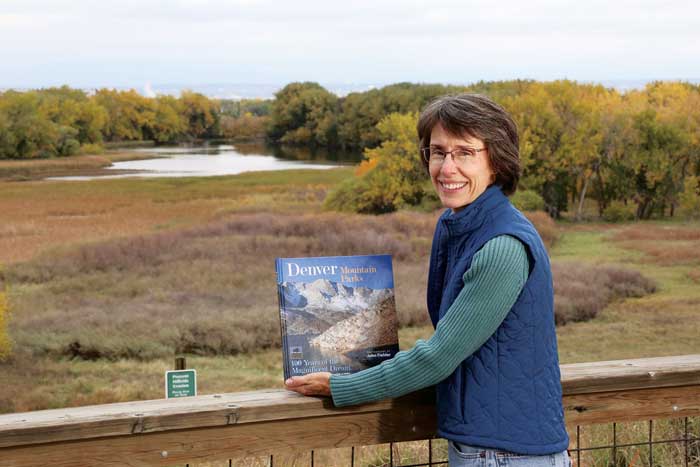

Standing at Bluff Lake Nature Center, Erika Walker is the author of a new book about her great grandfather, John Brisben Walker. He was a Denver civic leader who convinced Mayor Speer to create the Denver Mountain Parks system in 1910.

The most extensive, magnificent system of parks possessed by any city in the world,” trumpeted a full-page ad in The Denver Post in 1910. It announced the vision of entrepreneur John Brisben Walker and his partners to create a system of mountain parks just west of the city.

In 1913, the first of the Denver Mountain Parks, Lookout Mountain’s Lariat Trail, opened to the public. This year the parks are celebrated with a new book, Denver Mountain Parks: 100 Years of the Magnificent Dream, co-authored by Stapleton resident Erika Walker, the great-granddaughter of John Brisben Walker.

“There’s never been a complete history about the Denver Mountain Parks,” said Walker. “Given the centennial, it was long overdue.” The book is also a guidebook to the parks, including Red Rocks, Lookout Mountain and other favorites. Walker collaborated with writers Sally White, a cultural historian at Denver Mountain Parks; and Wendy Rex-Atzet, PhD, who wrote her dissertation on the parks. Colorado photographer John Fielder contributed 50 new photos and 25 “then-and-now” photo pairs for the project and published the book.

The Denver Mountain Parks are a 14,000-acre patchwork of open spaces, connected to open spaces owned by Boulder and Jefferson County. Most of the parks are within 30 minutes of Denver.

“Most of the mountain parks are so close they can be enjoyed in a half-day outing,” Walker said. “Sixty-eight percent of Denver residents use them; yet many are unaware they are Denver parks.”

The parks system ranges over four counties, at altitudes from 6,000 to more than 13,000 feet. It contains a series of loop-and-spur scenic drives connecting more than 40 named parks and unnamed parcels. The parks are listed on the National Register of Historic Places. In addition to the 22 parks developed for visitors, the system includes 24 undeveloped conservation areas closed to the public.

Walker said the book aims to educate and build support for this important resource. “The Denver Mountain Parks offer tremendous recreational opportunities and close access to the mountains,” she said. “They are also a portal to Colorado’s history. They need the advocacy of citizens.”

Walker’s favorite attractions for visitors include buffalo, dinosaurs and visible connections to the Old West.

“The dinosaur tracks at Red Rocks Park are 300 million years old,” she said, adding that the easy trails at Red Rocks make it a good choice for families.

Herds of buffalo in two mountain parks attest to successful efforts to prevent their extinction from overhunting.

“The buffalo were almost extinct by 1900, so in 1903 the Denver Zoo bought some cows,” Walker said. “In 1914, two bulls were brought from Yellowstone. Today herds of about 50 adults live in Genesee and Daniels parks; their numbers augmented in the spring with calves. They are some of the most purebred buffalo in the country and so some are auctioned for breeding.”

A preserved connection to the Old West is found at Daniels Park, where Kit Carson built his last campfire.

“Kit Carson was an advocate for the Indians, and he went to Washington, D.C., in 1868 for treaty negotiations. He was on his way back home to southern Colorado by wagon, and he was not well. He stopped in the hills outside Denver and built his last campfire. The next day he traveled on, and when he got home, he died. You can still drive the old wagon road in Daniels Park, with the site of the campfire marked. The wagon road is not covered with condos. It’s significant because Kit Carson’s death symbolized a time of the end of the expansion of the West.”

Walker is a self-taught naturalist and volunteer educator. A fourth-generation Coloradan, she lived with her husband in Minneapolis for 28 years before returning here in 2008. The family moved to Stapleton in part because of the nearby open spaces. Walker is vice president of the board of directors at Bluff Lake Nature Center.

She said her love of nature and Colorado history began on childhood camping trips with her family. She used great-grandfather Walker’s writings as source material for the new book.

“J.B. [John Brisben Walker] was part of a business group that took the idea of the mountain parks to Denver citizens,” she said. “Mayor Speer was seeking ways to fund the project. A mill levy was taken to the vote and won by a large margin.”

J.B. Walker was an entrepreneur who came to Colorado in the 1880s and introduced alfalfa as a cash crop. He bought property in Highlands, just north of downtown, and developed an amusement park, including a riverboat in a dammed section of the Platte River near Confluence Park. In 1883, he went to New York and bought Cosmopolitan magazine, then a literary publication that featured the work of writers such as Mark Twain.

J.B. Walker sold the magazine to William Randolph Hearst and moved back to Colorado in 1905. He bought 4,000 acres around Morrison, determined to make Red Rocks a tourist attraction to compete with Colorado Springs’ Garden of the Gods. He built foot trails, ladders, an observation deck, and an incline railway up Mount Morrison.

Once the Denver Mountain Parks project was approved, J.B. Walker worked with city leaders including Warwick Downing to hire landscape architect Frederick Olmsted. Olmsted rode the area on horseback to claim the best views for the parks. The group’s vision was to set aside 40,000 acres for the parks.

“Ultimately, they were able to acquire only 14,000 acres, but combined with the Jefferson County and Boulder open spaces, it’s about 40,000. So their vision was fulfilled. It’s a call to continued visionary leadership today.”

Maintaining the Denver Mountain Parks as a resource for citizens has been a challenge since the 1950s, when dedicated funding was discontinued.

“Now funding comes from the general budget, so the mountain parks compete with the city parks,” Walker said. “The mountain parks get short shrift because they are outside the city limits, so no city council member is responsible to advocate for them. It’s a struggle financially.”

In 2008, the Denver Mountain Parks Master Plan, spearheaded by then-Mayor John Hickenlooper and Denver Parks and Recreation, researched options for the ownership and management of the mountain parks.

“The research confirmed that charter and deed restrictions would make selling the parks extremely difficult, if not impossible,” said Walker. “And even if they could be sold, they would need to remain parks. Additionally, research confirmed that voters would have to approve such a sale and they would be unlikely to do so. The master plan concluded that Denver should retain ownership and management of the mountain parks and renew its commitment to them.”

The master plan recommended funding strategies including building collaborations with neighboring cities and optimizing existing revenue from the mountain parks, such as parking at Red Rocks.

Walker suggested ways citizens can help ensure the parks’ health, including contacting city council representatives, volunteering, or providing financial support—including buying the new book, which helps the parks’ coffers.

“It’s good to look back, and also to look forward to what the parks can become in the next 100 years,” Walker said.

For more information and to purchase

Denver Mountain Parks: 100 Years of the Magnificent Dream, go to www.mountainparksfoundation.org. To volunteer, contact www.denvermountainparks.org.

Love the new website! So great to be able to link to stories.