Terri Gentry, engagement manager for Black communities at History Colorado Center and docent with the Black American West Museum & Heritage Center, led Swigert third graders on a tour of Denver’s Five Points historic cultural district in February as part of the students’ Black history studies.

Even as some schools and school districts around the nation have gutted their Black history studies, students at Swigert International School marked February as Black History Month “by celebrating the assets and beauty of Black culture,” says third grade teacher Lindsay Edge. “It’s important to tell the first part of the story—the kidnapping of Black people from their home in Africa and enslavement—but not to stop there.”

Left to right: Chloé Fish, Avery Duncan, Olivia Waas, and Ethan Li, all third graders at Swigert International School, brainstorm ideas for their “take a stand” opinion pieces on a local or global issue, written in response to their Black history studies during Black History Month.

The Swigert third grade team has been developing its Black history unit since 2021. This year the unit covered the arrival of enslaved Africans to American colonies in 1619, the Civil War, Reconstruction, the Great Migration, and finally, the resistance and joy of the Harlem Renaissance.

Third grader Avery Duncan says the unit taught her “that it’s important to know how other people feel because if you don’t know, you can’t really fix it.” Her fellow student Olivia Waas agreed, saying, “When you know what the history was and what people have been through, you can help.” Many students expressed outrage or frustration over Jim Crow laws even as their schoolwork “helped them discover the importance of listening to others’ stories and telling your own story,” says Racha Kobitary, a former software engineer who is student teaching in Edge’s classroom as she earns a degree in education.

Third grader Avery Duncan says the unit taught her “that it’s important to know how other people feel because if you don’t know, you can’t really fix it.” Her fellow student Olivia Waas agreed, saying, “When you know what the history was and what people have been through, you can help.” Many students expressed outrage or frustration over Jim Crow laws even as their schoolwork “helped them discover the importance of listening to others’ stories and telling your own story,” says Racha Kobitary, a former software engineer who is student teaching in Edge’s classroom as she earns a degree in education.

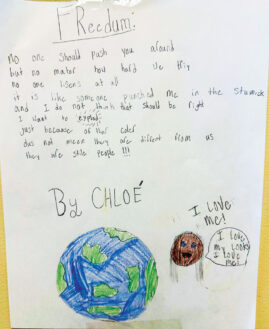

Throughout February, third graders read books on African American leaders, tried their hands at art and poetry in the style of the Harlem Renaissance, and even learned steps to the Charleston, a dance popularized by Black youth moving north in the 1920s. In one of her poems for the unit, Chloé Fish wrote that she feels she might “explode” when thinking about people being mistreated in response to their skin color. “All people should have the right to do their thing,” she says.

Swigert principal Shelby Dennis notes, “This isn’t a typical third grade social studies unit, and as an IB (International Baccalaureate) school, our teachers have really created an authentic and meaningful experience. It helps to show our young students the importance of individuals sharing their talents and stories and how that impacts historical and present-day society.”

Chloé’s poem “FReedum” from her school’s Black history unit.

This was the first year students were assigned a “take a stand” opinion piece as part of the unit. Students brainstormed how they could affect change before composing essays on topics such as homelessness, immigration, bullying, and the environment. Ethan Li says he wanted to write about the cost of housing because “when I think about other people, I can’t imagine what it’s like if I couldn’t afford my house.”

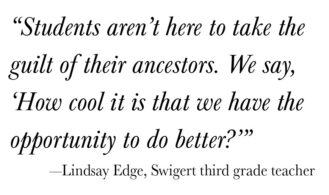

Edge explains, “For our two or three Black students in the classroom, once they see that this (unit) is not just going to be a story of oppression and misery but instead see their history and culture placed on a pedestal and admired, it feels great.” Of her White pupils, she adds, “Students aren’t here to take the guilt of their ancestors. We say, ‘How cool it is that we have the opportunity to do better?’”

This was also the first year the unit culminated with a field trip to Five Points, dubbed the “Harlem of the West” and once a hot spot for performances by Duke Ellington, Ella Fitzgerald, and Billie Holiday. Terri Gentry, engagement manager for Black communities at History Colorado Center and docent with the Black American West Museum & Heritage Center, led students on a walking tour through the historic cultural district. “Learning these stories teaches us to understand our present and envision our future,” she says. “It transforms our experiences from being invisible to sharing a collective memory, giving us a voice in our present, and a seat at the table to direct our future.”

Parents have been supportive of the history studies, though Edge acknowledges, “I could lose my job if I taught this unit in another state.” She previewed the unit on Back to School Night to give plenty of time for feedback. Several parents have used the lessons to spark conversations at home, and Black parents have said they appreciate their child “is learning about people who look like them in such a complete and positive way,” recalls Edge.

Caroline Dane, Swigert IB coordinator and mom to two students at the school, loves that her children are studying history from a “super relevant and powerful” perspective. “I am grateful this generation will have the empathy, awareness, and understanding that this unit lays the groundwork for.”

When Edge asked her students if parts of Black history were “too sad to learn,” she says, “they overwhelmingly said, ‘It’s our responsibility to learn this, to change, and to respect the culture.’” Kobitary, who herself is an immigrant from Syria, says “Our students are learning that their voice matters.” Teaching Black history has been “a reminder that every person has the power to create change.”

Front Porch photos by Christie Gosch

0 Comments