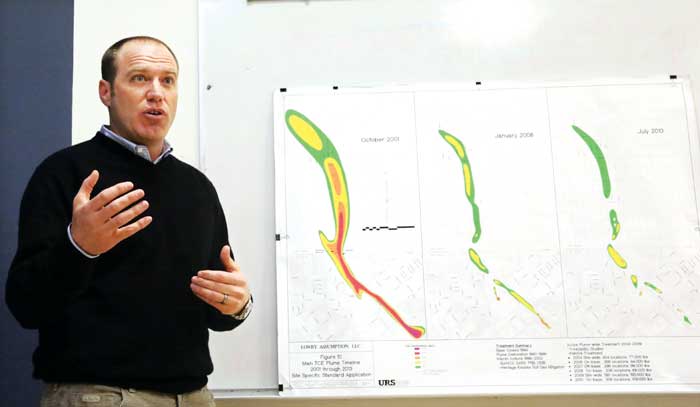

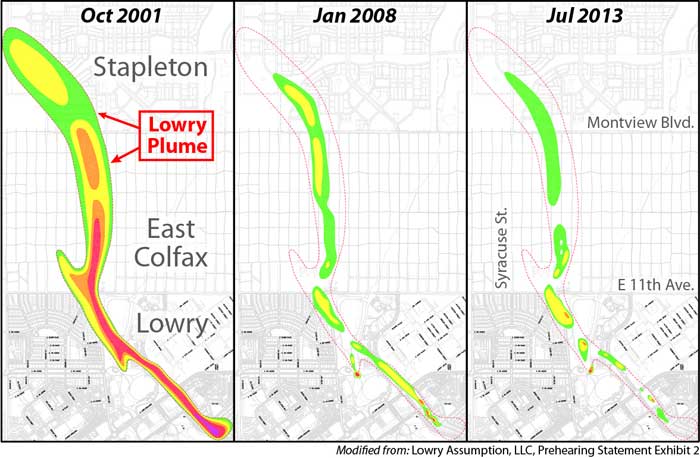

John Yerton is the head of remediation and investigation for Lowry assumption, LLC—the company responsible for remediation of the Lowry plume, which is shown in the chart behind indicating the plume has decreased from 2001 to 2013 (left to right).

Our house overlies the vestiges of an old chemical spill. The school behind us does, too. The spill’s poisons can cause life-changing illnesses. Yet we bought our house knowing about these contaminants. Why didn’t we avoid this location?

Because these contaminants, like most others, have been well-characterized and are under control. They’re part of an underground plume – one of thousands that underlie Colorado’s landscape. Our plume tells a story that may be common to your neighborhood, too.

What’s a plume? It’s an elongated area where soil, air, water or rock has been contaminated with another substance. You’ve seen ‘em before. After blowing out a candle, a plume of smoke soon emerges and wafts downwind. A factory spewing green gook into a river creates an ever-widening plume of contaminated water downstream.

The same thing can happen in underground settings where water regularly seeps between soil particles and bedrock cracks. Like giant slow-moving subsurface streams, this groundwater flows downhill toward lower elevations. It can transport plumes of hitchhiking contaminants from one area to another.

Underground plumes exist in big cities, in small towns, in the mountains, and on the plains. They originate in places where fluids were poured or leaked into the soil. Examples include old gas stations, dry cleaners, factories, mining sites and government facilities. Although plumes are common, most of Colorado’s groundwater remains clean. Where waters have been tainted, their plumes are generally well studied and remedied.

A common plume contaminant is trichloroethylene, or TCE. It was primarily used for removing oil and grease from machine parts. TCE is heavier than water, so it sinks to the bottom of water-saturated sediments in the subsurface where it steadily mixes with groundwater. Above the top of the groundwater, or water table, it can become a vapor and then burble upward through soil where it reaches the atmosphere. There it breaks down into harmless substances upon encountering sunlight and oxygen.

It’s a good thing our neighborhood doesn’t use the groundwater under our homes – it’s got TCE in it. Health problems can arise if you drink or bathe in water contaminated with TCE or if it wafts up into your basement in vapor form and you breathe it. With long exposure or high doses, TCE can cause cancer and disease, including to fetuses and reproductive systems. See ehp.niehs.nih.gov/1205879/

How’d TCE get under our house? A few miles south of here, TCE was used for several decades at a firing range, maintenance building, and fire training area at the old Lowry Air Force base. Over time, TCE worked its way into the subsurface from leaking tanks and a septic system. As the TCE migrated from Lowry the toxin became diluted by mixing with groundwater, by addition of rainwater, and by its natural volatilization into vapors that escaped upward into the atmosphere. Once discovered in the 1980s, the plume’s sources were addressed, and thousands of wells and borings were generated to determine the nature and extent of the problem.

But how is it being fixed? At first, groundwater was removed and treated near the sites of the original spills. More recently potassium permanganate, a purple salt used in water softeners, has been used. It converts TCE molecules into other harmless compounds. It was injected into the soil adjacent to and downslope of the original spill areas – creating a chemical defense line surrounding and downstream of the areas of highest contamination. Within the last nine years, Lowry’s TCE levels have dropped. In offsite areas that were ‘downstream’ of the initial contamination, TCE levels also dropped. Levels continue to decline, and in many areas the groundwater and the indoor air above the plume are safe. Where groundwater levels remain high, basement ventilation systems remove TCE vapors to keep people safe.

How safe is safe, though? Based on the EPA’s and Colorado’s environmental standards, our probability of being impacted by the plume’s vapors is similar to the probability of being hit by lightning in a given year.

Interested in learning more? Look at historical photos of your neighborhood and see what’s been around. You might be surprised. If you suspect there might be contaminated groundwater or soil nearby, contact the state health department (cdphe.state.co.us).

To determine if you live over the Lowry plume, refer to the plume map and FAQ below. If you have concerns, you can participate in the May 12 public hearing regarding future handling of the Lowry plume. www.lowryafbcleanup.com/web-page.html

James W. Hagadorn, Ph.D., is a scientist at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science. Suggestions & comments welcome at jwhagadorn@dmns.org

The Lowry Plume: Frequently Asked Questions

Evolution of the Lowry TCE plume: Pink areas indicate >1000 ug/L TCE in water, red >100 ug/L, orange >46 ug/L, yellow >18 ug/L, and green >5 ug/L.

What areas are impacted? Lowry, East Colfax, southwest Stapleton.

I see that TCE is below us but how much is there? What do units like µg/L and µg/m3 mean? These units are ways of measuring the amount of a substance dissolved in groundwater or in air, respectively. They’re both comparable to parts per billion. A part per billion is equivalent to about a drop of water in an Olympic-size swimming pool or a blade of grass on a football field.

Egads – the map shows TCE levels above the EPA standard of 2.1 µg/m3 below my house! The map is showing TCE levels in groundwater, not in your house’s air. TCE levels in the air result from the conversion of groundwater into a vapor or gas, and the resulting levels of TCE in the air tend to be much lower than those in the groundwater. When indoor air has TCE concentrations greater than 2.1 µg/m3, action must be taken. For example in Lowry, vapor removal systems are required in many homes. In homes that have been studied north of 11th Avenue (i.e., the northern limit of the Lowry base) airborne TCE levels are lower than this threshold level.

On the middle map, I see that at one site the TCE levels in groundwater increased rather than decreased. Should I worry? No. Such levels can vary due to many factors. Thus maps produced in the same month each year could show seemingly substantial variation depending on how wet or dry it was, depending on whether or not there had been a recent groundwater treatment, and/or depending on how much TCE detached from soil particles in different parts of the subsurface. The year-after-year average trend is of decreasing TCE levels in downstream plume areas. The map’s localized increase does not represent an error or a significant trend in the data. In short, don’t sweat it.

Can’t the groundwater rise if we have a wet year and bring TCE closer to my basement? Yes, but not enough to make a difference in your health risks. Water levels in this area typically vary by less than a couple of feet per year, even in extremely wet years.

Do I need to have a radon removal system to remove TCE vapors from my home? If you live over the TCE plume in Lowry – yes; but if you have a basement you likely already have one. If you live over the plume in East Colfax or Stapleton – no. That said, everyone in this region ought to have their basements tested for another toxic gas – radon. It is a naturally occurring gas that is common here, and your nose can’t detect it. The average Coloradan’s radon risk is over a hundred times higher than the airborne TCE risks associated with the Lowry plume.

But there are so many pregnant women and babies here. Doesn’t that make us more susceptible? No. We don’t use the groundwater – not for drinking, not for bathing, and not for the lawn. Basements downstream of Lowry and ventilated basements in and near Lowry have air TCE levels so low that fumes, if any, are a non-issue. Outdoor air levels are not a significant risk either.

Do I need to worry if I live above or near the plume? No, but see above. None of the water you use comes from groundwater in this area. Using such water is prohibited.

Aren’t there still a couple of drinking water wells around? No. The Colorado Division of Water Resources ordered the two abandoned irrigation wells in East Colfax to be closed and sealed.

I’ve heard that the EPA and/or Colorado standards are changing. Is it true that the TCE levels used for determining when it is OK to stop monitoring the downstream plume will soon be outdated or reduced?: No. Colorado’s state health department periodically evaluates and revises its environmental standards, but they did not indicate that a changing of standards was in the cards.

The models used to understand how TCE volatilizes beneath basement slabs are based on too few data points or have too large error bars to be reliable: Vapor intrusion can vary in response to many factors and there is always some uncertainty. Whereas eight to fourteen homes from East Colfax were used to characterize sub-slab vapor and indoor air conditions, they are located in what was the highest concentration portion of the downstream plume. Both the empirical (=observed) and modeling (=theoretical) work yield results that are internally consistent with results observed at many other sites. If anything, the Lowry plume is one of the best-studied, best-modeled, most well-understood plumes in the region. Its nature is controlled by the subsurface geology, which has been characterized in detail using thousands of subsurface wells and borings and analyses performed over a 30+ year period.

How can we be sure that we have accurately characterized the plume? You can have the highest level of confidence that this plume has been studied in gory detail, and that the best available practices have been applied. The Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, the state agency in charge of oversight for the cleanup, carefully reviews all the work done at Lowry. They can be reached at (303) 692-3303.

Is the proposed site specific standard just an attempt to lower standards or avoid dealing with the problem? No. The plume’s sources are being fixed (i.e., remediated), and the ‘downstream’ impacted areas (mostly East Colfax and Stapleton) are gradually remediating themselves. In the areas downstream of Lowry, the natural rate of breakdown is the same as would occur if additional remediation were attempted. Thus, short of digging a hole triple the size of Broncos Stadium and removing all the buildings and soil atop the plume, no reasonable additional or alternate treatment techniques will make the TCE go away faster. Because nobody drinks, bathes or waters the lawn with the groundwater, and because there is minimal indoor air risk from the plume’s fumes, it would thus be imprudent to spend additional money to try to decontaminate the downstream water and soil. In 10-20 years, mother nature will have done it for us, to the point that environmental scientists will barely be able to tell that there ever was a plume in downstream areas. In the Lowry source area, the situation is more perplexing. There is effectively no pore space available in the soil into which more potassium permanganate or other remediation compound can be injected – the soil is already stuffed full of such TCE-disintegrating fluids. It isn’t clear if additional remediation will be needed there, but if it is, another approach might be required.

Is adoption of a ‘site specific standard’ an environmental shortcut? Is it a conspiracy to save money and pocket the projected savings from the cleanup funds as profit? No. In fact, adoption of this standard will save you money and free up private companies and government watchdogs to work on other emerging environmental issues.

Who’s paying for all this? Your federal taxes paid the Air Force to make the spill, and your federal and state taxes are paying for the cleanup. Cleanup efforts are being accomplished by a partnership in which remediation is spearheaded by the Lowry Assumption Corporation and oversight is led by the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment.

Are there other plumes in my neighborhood? Yes. But they are generally smaller, are not under buildings, and/or have already been remediated.

I live in lowry and have been smelling a chemical outgasssing from our basement for the last 2 years when our unfinished basement floor got wet from the ground watter. I have become very sick in the last year. How can we test for the chemical smell that is coming from the basement? And is there a way to test blood or urine for a chronic low level exposure?

Pls reply to tiffbinder@hotmail.com I am very sick and need help!

Hi Tiffany,

Since this article is 8-years old, I am going to refer you to the CO Dept. of Public Health and Environment page which is monitoring this situation. At the bottom of the page, there is a CONTACT link which would get you to an actual person to contact. Good luck! https://cdphe.colorado.gov/lowry_afb

I'm glad that King Soopers admits that the Quebec store is over capacity. Clearly the store has been stretched to maximize profits at this location with the belief that they (King Soopers) can swoop in at any time and build another store at Eastbridge when they reach the breaking point, which has apparently finally arrived. Since they have the first right of refusal and are clearly in need of more capacity, what other grocery store (Trader Joe's, Sprouts, Natural Grocers etc.) is going to want to go through the trouble and cost of market research, site design, architecture and the public process if King Soopers can and will come in and pull the rug out at any time. Forrest City made a bad deal for the neighborhood with the first right of refusal clause and we are paying for it. The assertion that the Eastbridge site has no housing immediately to the north and therefore cannot handle a smaller store (natural market or otherwise) but can somehow magically handle a much larger store is absurd. Furthermore, Natural Grocers (Vitamin Cottage) is about to start construction of a new store in Golden on the edge of a vast tract of open space (South Table Mountain), in an area much less dense than Stapleton.

Hi, Doug. The writer James Hagadorn is the best person to talk to at jwhagadorn@dmns.org.

Where can one find a truly DETAILED map of the Lowry Plume? The one displayed online references only four streets…