Word of mouth during the pandemic doubled the number of youth coming to FullCircle, which offers free support meetings for youth and parents from around the metro area.

“It’s probably worse than you think,” says Alex,* when asked what parents should know about youth drug use. Alex began using in sixth grade, moving from vaping tobacco to marijuana within weeks. In Alex’s experience, drug use doesn’t “plateau,” but escalates, and in Alex’s case, it led to a nearly deadly overdose.

“If you start doing drugs you’ll probably like them. That’s the problem,” says Ben Stincer, who directs the FullCircle youth recovery and support program premised on “the idea that young people will stop their self-destructive behavior only if they are offered an alternative that is both fun and fulfilling.” Front Porch photo by Steve Larson

Alex’s addiction grew quickly. “It went from weed [to] selling weed, and then it went from smoking weed with like maybe crack on it, sometimes like crazy stuff and then it went to Xanax and all this other stuff and selling drugs and it just snowballed so fast.” Alex spent the better part of two years high on one substance or another, selling and stealing to purchase drugs and using turpentine and even hand sanitizer to get high when nothing else was available. “Kids are very easy to manipulate,” Alex shares. Once, “I thought I was doing Percocet. It was fentanyl. I was manipulated many ways, being a kid in the drug scene.”

During the long early days of the pandemic, Alex’s parents were happy that Alex was spending a lot of time outside with friends rather than in front of a screen. They checked in frequently and didn’t suspect much because by the time Alex returned home, the LSD or other substances had worn off. When they did become concerned, they discussed things and implemented consequences. They had “frank conversations,” Alex says, but also notes that these resulted in a “false sense of trust.” After failing a marijuana, test to avoid getting grounded, Alex says, “I didn’t really care too much for weed…so I gave them my weed, so I could go out and do a different drug.”

Ben Stincer, who directs FullCircle, a nonprofit that works with teens with a variety of issues, says it’s not unusual for parents to be caught unaware, because youth are really good at hiding what they want to keep hidden. Though there may be behavioral changes, “on some level, you don’t know until they tell you, or until something happens,” says Stincer. “It starts out with a very simple thing: you get high one time, or you self-harm one time, or you starve yourself and purge or something of that nature….And at that point, it’s just this one little thing they did. But as they started to do it more and more, now it’s a quarter of their life. They do it more and more. Now it’s half, and if they start doing it all the time, that’s the entirety of their lives that they’re telling their parents nothing about.”

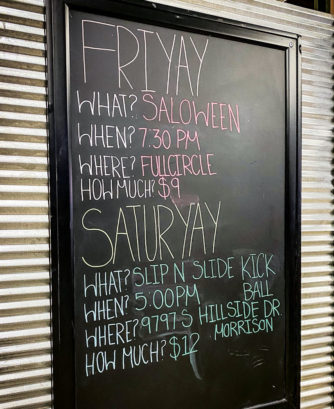

FullCircle is a twelve-step program, illustrated by the staircase. Though started as a ministry of the Catholic Church, the Denver program receives no Church funding, relying instead on foundations and private donations. Youth attend two weekly support groups and two weekly sober socials, and parents attend one weekly meeting. A youth contract and parental involvement are critical to success.

Though Stincer sees drug use as very normalized, it paradoxically still represents a form of rebellion for many teens, who are trying to define who they are. Social media makes access easy, with both Snapchat and Facebook commonly used for communicating with “plugs” (dealers).

No transportation? No problem. Alex’s mom shares that “The drug dealers are just driving right up to the town center and right across from the skate park in the neighborhood….They deliver.” Alex’s dad compares the service to Uber Eats.

“Sober social” events cap each week. Stincer hopes the kids’ social media posts reach “the kid that’s sitting at his house smoking pot,” who maybe thinks ‘that looks way more fun than what I’m doing,’” says Stincer.

On the day of the overdose, Alex recalls telling the dealer “’Bro, you’re late and I’m already buying a lot of stuff. You owe me something….’ So he gives me like a good amount of Xanax. Me and my friends split it. And then we go home…I didn’t even feel anything, you know, it was like ‘Okay, like these aren’t working. I’m just gonna go to sleep, that’s it. And I just don’t wake up.” Unable to rouse Alex for school the next day, Alex’s parents raced to the emergency room. Alex recalls little but “screaming at my parents, random s&*t, because Xanax makes you a piece of s*7t.” Within a week, Alex was at a rehab program that his parents credit with saving their child’s life.

After the three-month rehab program, Alex started going to FullCircle, a support group for youth and parents. The peer community provides a strong foundation while also offering a social outlet that is “as much fun as I had doing drugs.”

Fun is embedded in the idea of “enthusiastic recovery,” the group’s philosophy. “There are two kinds of drugs,” Stincer says, “good drugs and great drugs. And the problem is that they feel really good.” He remembers the many challenges and anxieties of being a young teen. “I was 13. I smoked a joint, and I remember thinking ‘Everyone that’s ever told me not to do this was lying, and they’ve never done it because this is awesome!’” FullCircle works to offer youth something “equally exciting or as visceral as that lifestyle can be while helping parents hold their walls and supporting them with the program,” says Stincer.

Sobriety is a daily commitment. Long-term peer support is critical to maintaining that commitment. Coming out of rehab, Alex says, “you’re like a baby….you’re living a completely new lifestyle and you have no idea how to do it.” Now on step 7 of the 12-step program, Alex hopes to someday become a sponsor to a younger teen on their road to recovery in FullCircle.

To learn more about FullCircle, call 720-531-3716 or visit www.fullcircleprogram.com

*Alex is a pseudonym.

Photos of FullCircle by Christie Gosch

Do not send your kids here. The philosophy is questionable and the program has a long history of controversy. Please go to Enthusiastic Sobriety Abuse Alliance for more information before introducing your kids to this program. Look for qualified medical help instead.