Using the VirTra V-300 simulator at the police academy, officers (Sergeant Eric Knutson in the foreground and Technician Dan Marsh in the background) are confronted with scenarios that resemble an active shooter situation to reinforce both single officer training and a team approach. Front Porch photo by Christie Gosch

The recent Uvalde shooting was a tragic reminder that we have come to expect that police now know how best to respond to a school shooter and will act based on the latest and best conclusions of law enforcement and education professionals. The delay in Uvalde that cost additional lives led us to ask spokespersons from Denver Police Department (DPD) and Denver Public Schools (DPS) about their readiness for such an event.

Moments after any threatening event occurs (including an active shooter threat/school lockdown), DPD calls for a “hotwash”—a team debriefing on exactly what happened, what went well, what can be improved—says Division Chief Ron Thomas. About a week later, that’s followed by another debriefing when more facts and in-depth information have been gathered. Thomas says DPD officers are used to responding to threats and they train regularly in both single officer and team responses to threatening events. “We may need a single officer to respond to some kind of active shooter or violent incident on their own. And so we trained them on how to do that. We also train on IARD (Immediate Action, Rapid Deployment)…a team approach. We’re not waiting for the SWAT team or some specialized unit to respond and take action, we’re really just formulating teams of the first officers to arrive on scene.”

Moments after any threatening event occurs (including an active shooter threat/school lockdown), DPD calls for a “hotwash”—a team debriefing on exactly what happened, what went well, what can be improved—says Division Chief Ron Thomas. About a week later, that’s followed by another debriefing when more facts and in-depth information have been gathered. Thomas says DPD officers are used to responding to threats and they train regularly in both single officer and team responses to threatening events. “We may need a single officer to respond to some kind of active shooter or violent incident on their own. And so we trained them on how to do that. We also train on IARD (Immediate Action, Rapid Deployment)…a team approach. We’re not waiting for the SWAT team or some specialized unit to respond and take action, we’re really just formulating teams of the first officers to arrive on scene.”

Division Chief Ron Thomas says, “We feel the amount of regular physical and virtual practice we do now is sufficient.” File photo by Steve Larson

For school shooter training, police officers participate in a quarterly review of IARD, which Thomas says is “often partnered with different public schools to do kind of a mock scenario…a real time drill where we have actors and we have officers clearing classrooms….There’s a tremendous workload, managing calls for service, but we still try to carve out time for training officers so that we can keep our skills fresh. We make sure that officers know where they can find the plans…how to set up a response for a particular school in each district…We feel the amount of regular physical and virtual practice we do now is sufficient, reinforced by our successful response two weeks ago” (a shooter threat and lockdown at Northfield High School on May 26*).

Likewise, following Uvalde (and the Northfield High School lockdown two days later), DPS is investigating what they can learn and how they can do better. DPS Director of Emergency Management Melissa Craven cites the need for all internal, as well as external, doors to be locked and secured. In 2016, DPS replaced all interior door locks with locks that secure from inside the classrooms, but with thousands of doors, the district continues to find and fix locks. Craven adds, however, that doors don’t stay closed all the time. “If it’s warm in the building…they probably open a door to get the breeze.”

Park Hill Elementary School, like many other DPS schools, has numerous classroom doors that open directly to the outside. Any problems or difficulties with locks that arise during drills are quickly corrected, says Principal Ken Burdette. Front Porch photo by Christie Gosch

Park Hill Elementary School Principal Ken Burdette says DPS has drills at the beginning of every semester for lockdown (when the threat is inside the building) and lockout (when the threat is in the surrounding area of the school). Before the drill, students watch an instructional video. “Locks, lights and out of sight” is the safety motto.

When the alarm sounds, teachers manually lock the doors from the inside and turn off the lights, says Burdette. Simultaneously, everyone moves out of sight from the windows. No blinds are drawn and no phones are turned on or off. Burdette and the assistant principal walk the halls, checking that each door is locked. They also look through the windows to be certain nobody can be seen. The lockdown and lockout drills take approximately 15 minutes; then an announcement over the PA system indicates the drill is complete. Any defective locks are fixed by the following day.

When Burdette started as principal at Park Hill more than eight years ago, he says not every door could lock from the inside—now they all do. And DPS Safety provides training for principals so they can train their staff. “I would say it’s treated more thoroughly and more urgently than when I started years ago.”

While the drills are necessary, they still affect some students’ mental health. Parents have been outspoken about the possible trauma that the drills place on their kids, though DPS counselors and psychologists do provide mental health services to the extent they are available in individual schools. “There’s not one specific plan because it’s different for each child,” says Burdette, “but we do indeed work with the child and oftentimes with the parents.”

Craven says, “Nobody wants a child to have to go through them…and I’m certainly empathetic to that, [but] I would rather we deal with a child that is frightened, and have resources…to wrap around that child and get them through it…than have them be in a situation where they don’t know what to do.”

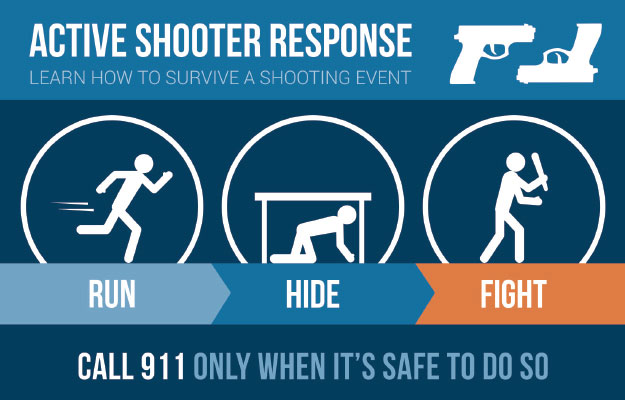

Since Sandy Hook, departments of the federal government have promoted the run, hide, fight response to a shooter. DPS uses the terms escape, evade, engage. Image from Shutterstock

The federal government adopted the run, hide, fight model after Sandy Hook, but most schools give “lip service” to the run part, while hiding is heavily encouraged for students and staff, wrote FBI Special Agent Katherine Schweit in an opinion essay for the New York Times. She also wrote that her friend Frank DeAngelis, former principal of Columbine High School, wished that his students and staff had been taught to flee.

DPS changed the language to escape, evade, engage, and they put a heavy emphasis on evade—securing the classroom during a lockdown. At Park Hill Elementary, the students only learn evade—locks, lights and out of sight. Engage and escape are taken into perspective only if all students can escape with a faculty member.

“The escaping piece of it can be a struggle for our younger learners. It’s hard to corral and move 20 or 30 elementary age kids,” says Craven, but she acknowledges high school students “have the ability to take on more responsibility for their well being than some of our younger learners.”

Thomas says he meets regularly with the DPS safety team to get reports on what DPS is doing and why in regard to lockdowns and lockouts. And over the coming year, as more debriefing reports are released from Uvalde, DPS and the DPD will continue to identify specific changes needed in their active shooter protocols.

*See Denver DA’s announcement on page 13.

0 Comments