Vietnam veteran Neal Stanley holds a photo of himself after he had served a year in Vietnam. During his deployment, he served as a medic on 746 missions in a “Huey” helicopter similar to the one behind him.

The helicopter was purchased in parts by the Minnesota Historical Society and restored by volunteers to be used for displays such as this exhibit. Stanley helped reassemble the helicopter when it arrived at the museum.

The first room in The 1968 Exhibit at the History Colorado Center brings visitors face to face with the scene above. A TV in a ’60s decor living room has Walter Cronkite reporting on the Vietnam War. A real Huey helicopter looms over the room and a casket sits in the corner—grim reminders that the controversial war was a very personal and painful experience in many American households.

As Vietnam veteran Neal Stanley stood next to the Huey on opening night at The 1968 Exhibit, passersby respectfully stopped and thanked him for his service—not even knowing he was a medic who went on 746 medical evacuation missions.

Stanley’s story of the Vietnam War had a happier outcome than many of his fellow servicemen, but it is a reminder of what the year 1968 was like for U.S. soldiers.

After a year of college, Stanley enlisted in the Army because that enabled him to choose his training rather getting assigned by the Army if he got drafted.

His thinking when he chose medic training was, “Why not be on a medivac helicopter as opposed to walking in the woods with the infantry?”

There was no GPS in 1968. “If we’d had GPS, it would have been a wonderful thing,” says Stanley. Everyone used the same FM frequency—and it was also known by the enemy. Field commanders often weren’t sure exactly where they were but gave grids and coordinates to the helicopter crew to the best of their knowledge.

Stanley says when the crew thought they were close, they would radio for the ground troops to throw a smoke grenade. Then the rescue crew would verify the color of the smoke. “If there was a big battle going on, we’d tell them ‘Throw another one,’ because we learned the bad guys were listening to the radio and they might throw smoke to try to lure us in to where they are to land and then shoot us up big time.” So they would verify that a second colored smoke bomb was really the location of their injured troops.

Not every mission was a war injury, says Stanley. “You’ve got guys living in bad conditions. Many guys hadn’t seen action in two weeks, but a guy falls down and breaks his ankle. And a lot of malaria, snake bites, spider bites. You’ve got everything that would happen if there wasn’t a war. But then you’ve got a war going on and once a battle starts you’ve got a boatload of stuff happening.”

All day every day during his year in Vietnam, Stanley flew on these rescue missions. His medals include a Silver Star, the third highest in the military, for gallantry in action. He also has a Bronze Star and 18 air medals, each of which represents 25 hours and 25 missions under combat.

After his military service, Stanley got a degree in engineering and worked in the oil and gas business. He currently volunteers his time with Boots to Energy, an organization that assists returning veterans in obtaining high-paying jobs in the oil and gas industry. For information, visit www.bootstoenergy.com.

Below view a gallery of displays from the 1968 exhibit where visitors can relive the events of that tumultuous year.

The sign at the entry to the exhibit flashes images of iconic events and people from 1968.

Martin Luther King was assassinated on April 4, 1968. Four years earlier he had been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his civil rights work. But he remained a controversial figure, constantly threatened and despised.

In April 1967, he began making impassioned anti-war speeches that drew millions more to his side while infuriating millions of others.

On April 4, 1967, he said, “So we have been repeatedly faced with the cruel irony of watching Negro and white boys on TV screens as they kill and die together for a nation that has been unable to seat them together in the same schools.” In the months preceding his death, Dr. King increasingly turned his focus from civil rights for African Americans to a more universal struggle for economic justice, for the rights of all Americans who were suffering from low wages, employment discrimination and poverty.

Walter Cronkite is shown reporting on the Vietnam War on a TV in a 1960s era living room setting. A huge Huey helicopter adjoins the living room, symbolizing the impact of the war in American households.

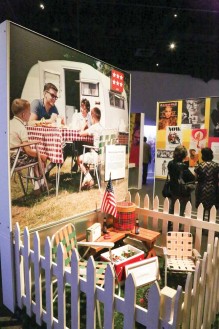

A camping trip photo and picnic scene portray a stereotypical image of life for a 1960s white family.

Kennedy had announced his intention to run for president on March 16, saying, “I run to seek new policies—policies to end the bloodshed in Vietnam and in our cities, policies to close the gaps that now exist between black and white, between rich and poor…I run because it is now unmistakably clear that we can change these disastrous, divisive policies only by changing the men who are now making them.”

Left side of photo: At the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico City, Tommie Smith and John Carlos raised their black-gloved fists during the U.S. national anthem at the medal ceremony for the 200-meter race where they won first and third—a gesture that became known as the Black Power Salute.

In September 1968, Stokley Carmichael, an activist with the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, became the “Honorary Prime Minister” of the Black Panther Party. Carmichael’s words from a 1966 speech in Berkley still resonated. “We are now engaged in a psychological struggle in this country, and that is whether or not black people will have the right to use the words they want to use without white people giving their sanction to it; and whether they like it or not, we are going to use the words ‘Black Power….We’re tired of waiting.”

I’m proud to call Neal Stanley a friend. We appreciate his service and that of his comrades. Great article.