Written on the Land: Ute Voices, Ute History at the History Colorado Center brings the story of Colorado’s longest continuous residents into present-day Colorado. Where the homeland of the three Ute tribes’ ancestors extended beyond current Colorado borders, today the three reservations are limited to the land areas shown above in orange (Utah), green and blue (southern Colorado). With a nod to their ancestral lands, the Ute speakers at an opening event greeted visitors with the words, “Welcome to our land.”

The new History Colorado exhibit about Ute tribes was a joint effort of tribal members and museum staff, which included: (from left) Betsy Chapoose, Ute Indian Tribe, Cultural Rights and Protection Director; Cassandra Atencio, Southern Ute Tribe, NAGPRA Coordinator; Ernest House, Jr., Ute Mountain Ute Tribe, former executive director Colorado Commission of Indian Affairs (CCIA); Shannon Voirol, History Colorado, Director of Exhibit Planning; Sheila Goff, History Colorado, Curator of Archaeology and Ethnography, NAGPRA Liasion; Liz Cook, History Colorado, Lead Exhibit Developer.

“Written On the Land”

Millennia before it became the Centennial State, Colorado was the home of indigenous people including the Ute tribes. Written on the Land: Ute Voices, Ute History at History Colorado aims to bridge the Utes’ history with modern-day Colorado.

Southern Ute Chief Buckskin Charley (1840-1936) passed this drum down to his son, Antonio Buck, Sr. (1870-1961). Below: Shavano Rock Art, near Montrose. The site, named for late-1800s Chief Shavano, preserves centuries of Ute carvings.

Ute saddle: Acquiring horses in the 1500s changed the Utes’ economic and social lives. They could hunt more large game, carry more goods and travel farther to trade and socialize.

“It’s cool to imagine what the Utes were doing in our familiar places, thousands of years before us,” said Shannon Voirol, director of exhibit planning at History Colorado and lead developer of the exhibit. “In metro Denver there are hundreds of sites that indicate the Utes’ presence, including near Bluff Lake.”

Written on the Land, a new long-term exhibit, was developed in collaboration with the Southern Ute Indian Tribe, the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe, and the Ute Indian Tribe of the Uintah and Ouray Reservation. History Colorado staff met with tribal representatives, including elders, historians, and culture and education experts, over four years to develop the content, Voirol said.

The last hereditary chief of the Southern Utes, Buckskin Charley, gave this headdress to his son, Antonio Buck, Sr., the first elected chairman of the Southern Ute Tribe.

Written on the Land displays more than 175 artifacts, including Ute beadwork, clothing, basketry and contemporary crafts. On view is the colorful beadwork that adorns dresses, moccasins, bags and jewelry, along with willow baskets, stone tools, and wooden saddles. Photos and videos show Ute traditions preserved to the present day, including the Bear Dance with its elaborate beaded gloves, fringed shawls and carved instruments.

“The tribes support this exhibit because it helps their kids and grandkids to know their stories. Also, they want Denver people to know about their lives,” Voirol said.

The exhibit explores iconic Colorado places where the Ute people resided for generations. “Pikes Peak is important to the Southern Utes, called ‘people of the shining mountains,’” said Sheila Goff, curator of archaeology at History Colorado. “The mountain is named tava-kahv in their language because it is one of the first peaks to get the sun in the morning.”

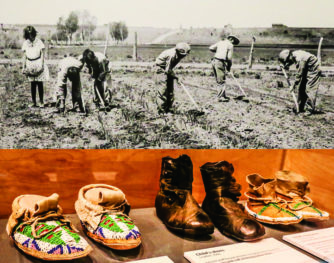

Ute children were required to go to boarding schools where they were taught farming. Their moccasins were taken from them and they had to wear shoes like those shown above.

The Utes’ original territory covered most of Colorado. They moved with the seasons, from the mountains in summer to lower elevations in winter. “Their movements were purposeful and practical, not aimless,” said Voirol. “They prefer not to be called nomadic.”

“Our history is written on the land. These places in the Rocky Mountains are where we connect to our history,” said Regina Lopez-Whiteskunk of the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe, a tribal representative who participated in the planning of the exhibit.

Forty-eight American Indian tribes have ancestral ties to Colorado. Some archaeologists say the Utes have been in Colorado for more than 13,000 years. “That time period is indicated by their material culture, such as their baskets,” Goff said. “Also their oral tradition tells us how they lived and where.”

Written on the Land brings history to the present and talks about the contemporary lives of Ute tribal members. Many Utes still live on three reservations: the Ute Mountain and Southern Ute reservations in southwest Colorado; and the Uintah and Ouray Reservation in eastern Utah. Others live in Denver as part of a larger community of American Indians from many tribes. “They’d like us to know they’re still here, so don’t think of them in sepia,” said Voirol.

Far left: Courtship flute: Flutes are an important part of the music of courtship. Left: Bag by Sophia Box, Ute Mountain Ute Tribe, 2003. Cut glass seed beads, leather, thread. Top right: Basket, Ute Mountain Ute Tribe. This weaver used traditional and contemporary techniques to show a nation within a nation. Bottom right: Basket, Ute Mountain Ute Tribe. This weaver used traditional and contemporary techniques to show a nation within a nation.

“We didn’t get wiped out, we didn’t move away, we’re still here and we will still be here,” said Terry Knight Sr. of the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe, who participated in the planning of the exhibit.

Shavano Rock Art, near Montrose. The site, named for late-1800s Chief Shavano, preserves centuries of Ute carvings.

Modern-day Utes are preserving their language and culture, as well as sharing their knowledge. Statewide, a National Science Foundation grant is connecting traditional Ute knowledge with science in an education program for schools and Ute tribes. Anthropologists, botanists, scientists and researchers are bridging their scientific knowledge with the traditional ecological practices of indigenous peoples.

Archaeological fieldwork surveys with Ute elders and youth are featured as interactive spaces in the exhibit, allowing museum visitors to learn more about the Utes’ use of plants.

0 Comments