Yesterday’s best practices can be today’s barrier to change. I think the problem is that when you’re trying to be a reformer…you have to be committed to the purpose and not to the method to get that purpose.”

-Dr. Howard Fuller, Ph.D.

In June, A+ Colorado, an educational advocacy organization, released “Start with the Facts: Denver Public Schools at a Inrossroads,” a report that examines the current state of affairs in Denver Public Schools (DPS) and recommends future directions.

A+ finds DPS lagging behind its goals, like having 80% of its third-graders reading at grade level by 2020. The report concludes that reaching the 2020 goals will take ten or more years past 2020, depending on the measure.

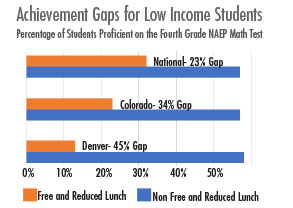

A concerning—and related—finding is that the “achievement gap,” the gap between low-income students and their more affluent peers or between White and non-White students, has persisted and, in some cases, grown.

For example, on a national test of 4th grade math, Denver is ranked third worst in the country among similar urban districts for academic gaps, with a 45% proficiency difference between impoverished students and their peers who don’t receive free and reduced lunch (FRL).

In a district that is 67% low-income and 77% non-white, such achievement gaps can prevent DPS from achieving 2020 goals for proficiency and graduation rates. What should DPS do to address these gaps and improve its performance?

Should DPS stick with the education reforms that have marked its last decade of progress? Is it time to return to a neighborhood schools model? Or are opportunity gaps simply impossible to repair?

As anyone who follows education knows, there are no easy answers to such questions.

DPS Shows Big Improvements in Achievement, Graduation Rates and College Enrollment

The District’s reform measures over the last decade have been largely successful, bringing what was once one of the lowest-performing urban school districts up to the middle of the pack, a considerable achievement.

- Since 2005, DPS enrollment has grown 27% across all grades, to 92,000 students, outpacing the growth of metro Denver as a whole.

- On the 2017 Colorado Measures of Academic Success (CMAS), DPS students of all backgrounds outperformed the state in both language arts and math and has shown higher year-over-year growth compared to the state as a whole.

- Over the last several years, the trend-line for DPS achievement on state exams has shown steady upward progress, while the state as a whole has remained relatively flat.

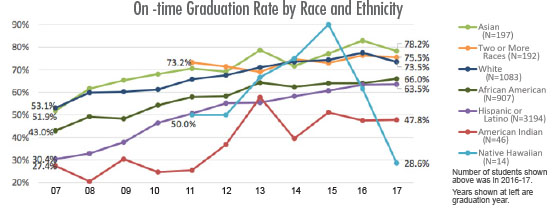

- Four-year graduation rates have risen to 67% in 2016-2017, compared to just 39% in 2006-2007, with a decrease in drop-out rates from 11% in 2005-06 to only 4.1% in 2016.

- DPS student college enrollment reached a record high in 2017, with 2,297 graduates – 51% – enrolling in the fall immediately following graduation, compared to just 1,324 students matriculating to college in 2007.

But do these impressive statistics tell the whole story?

Despite Successes, Criticism

Panelists at a recent A+ Colorado meeting debated the district’s progress, with some expressing deep skepticism at whether reform efforts have helped poor children in particular. Although all students at DPS have made strides, achievement gaps persist. Former school board member Theresa Peña repeated criticisms she’s expressed elsewhere, “We’ve changed every aspect, but the outcome for poor students hasn’t changed.”

Meanwhile, the influence of the teachers’ union is rising, with two union-supported candidates elected to the board last fall. In addition, some community organizations and parent groups seek to dismantle the reform system of charter schools, standardized testing and test-based teacher accountability, suggesting that school choice has not equitably benefited all students.

In particular, the outcry over school closures has been fierce. Critics contend a neighborhood school serves a function in a community that goes beyond performance on standardized tests. Recently, the school board responded by putting a “pause” on future school closures, though some question if that simply means kids will languish longer in low-performing schools.

Denver’s recent performance on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (the NAEP) exam was disappointing, showing that DPS students are only average, nationally. Current DPS Board member, Barbara O’Brien, while noting the significant improvement in outcomes at DPS, nonetheless emphasized that it isn’t good enough. “What needs to be done to take us from average to the top 25% of all districts?” she asked.

The answer to that question seems to lie in addressing opportunity gaps that appear worse in Denver than elsewhere. “The incredible acceleration of performance by white and affluent students at breakaway speed from peers of color should alarm every policymaker who cares about opportunity gaps,” states the A+ Colorado report, which suggests DPS is at “an inflection point.”

In a district where the vast majority of students are low-income and non-White, only policies that provide resources to those students will make a measurable difference in raising the district’s overall performance.

What Next?

Addressing the achievement gaps that drive many performance deficits at the district is not easy. Dr. Pedro Noguera, a national education expert, notes that “those gaps in achievement are common throughout America, so it’s not as though Denver is by any means an isolated example. A lot of it is about the way inequality outside of school shapes what’s happening to kids inside of schools.”

But, says Noguera, “Where the district has to be responsible is, what are they doing to ensure that schools that are serving disadvantaged kids have the resources they need?”

The A+ report makes a number of recommendations to help Denver improve its schools, including strategic planning to establish new goals for 2025, prioritizing diverse school model options, and urgently addressing the opportunity gap.

But how will DPS, renowned for its progressive education reform, proceed in overcoming the sharp divide between impoverished students and their better-off peers?

“I think the thing that we have to worry about is that [education reformers] could very quickly become the new status quo,” said Dr. Howard Fuller, one of the most prominent education advocates in the country. “For me, yesterday’s best practices can be today’s barrier to change. I think the problem is that when you’re trying to be a reformer…you have to be committed to the purpose and not to the method to get that purpose.”

Commenting on to future directions for the DPS board, Angela Cobián, the newly elected school board representative for southwest Denver proposed a “third way.” “I’ve had a lifetime of people putting me into boxes that I didn’t decide. So the idea…is that you create a third way, combining your experience as a person of color in public education with reform ideas,” said Cobián. “It’s a lot more ground up than what we do now and what we have done and also doesn’t totally reject the things that people who are not reformers say.”

DPS board members have expressed an intention to embark on a “listening tour” of Denver to understand more deeply the concerns of their constituents. But it remains to be seen whether they will continue with the reform process that has brought them this far or turn in a different direction in the quest to create equal opportunities for all students.

0 Comments