In this representation of the 1787 signing of the Constitution, Alexander Hamilton, in the front row, leans to speak to Benjamin Franklin; James Madison sits to his left, and George Washington stands on the podium. This 20-by 30-foot sailcloth painting by Howard Chandler Christy hangs in a stairwell in the House of Representatives. Photo from https://commons.wikimedia.org

Colorado enacted the National Popular Vote (NPV) interstate compact into law in March 2019. In November 2020, voters will see a question on the Colorado ballot asking if they choose to repeal this law. The NPV, when enacted by states with a total of 270 electoral votes, will ensure that the Electoral College vote will match the popular vote winner. The Founding Fathers shown above had long difficult debates on who should get a vote—and they created the Electoral College as “a buffer between the people and the president,” says Lois Court, former state senator and civics teacher. Hamilton wrote: This “intermediate body of electors, will be much less apt to convulse the community with any extraordinary or violent movements.” But the founders did not write into the Constitution how electors should be chosen—that right was left to the states. After two elections in the past 20 years in which the popular vote winner did not become president, 58% of US adults now say the candidate with the most votes should win.

Long before he was a rapping, swaggering Broadway sensation, Alexander Hamilton was an unapologetic elitist. To be fair, Hamilton was not alone among the Founding Fathers in this regard. The radical experiment that was our fledgling, fragile republic had to rely on wise and virtuous leaders to govern without self-interest tarnishing their commitment to the public good.

Long before he was a rapping, swaggering Broadway sensation, Alexander Hamilton was an unapologetic elitist. To be fair, Hamilton was not alone among the Founding Fathers in this regard. The radical experiment that was our fledgling, fragile republic had to rely on wise and virtuous leaders to govern without self-interest tarnishing their commitment to the public good.

Deeply afraid of government corruption, the founders believed that those lacking in property, education, maleness, and whiteness could more easily be led astray by demagogues preying on base self-interest and emotion. James Madison had studied ancient democracies and found them deficient for this very reason, observing in The Federalist Papers that even in these high-minded assemblies “passion never fails to wrest the scepter from reason.”

Why the Electoral College?

“The word ‘democracy’ does not exist in our founding documents; the founders didn’t believe in democracy. They believed in a republic. That’s a huge difference,” says former state senator Lois Court. Indeed, Founding Father Benjamin Rush called democracy “the devil’s own government,” while Gouverneur Morris equated the masses (commonly referred to as “the mob”) with “poor reptiles.”

A republican government, on the other hand, meant that while power resided in the people, protections—such as the coequal branches of government—would prevent “mob rule” and the tyranny of the majority over the minority.

“The founders created the Electoral College as a buffer between the people and the president,” says Court, who taught civics for years. In The Federalist Papers, Hamilton explains electors are needed to reduce the likelihood of “tumult and disorder” and “mischief.” This “intermediate body of electors, will be much less apt to convulse the community with any extraordinary or violent movements.”

Though the electors’ votes typically have aligned with the national popular vote, the Electoral College has become the source of increasing contention in the space of a single generation. In both the 2000 and the 2016 elections, the electors did not chose the popular vote winner. In 2000, the US Supreme Court stepped in to declare George W. Bush the winner. In 2016, the electoral vote went to Donald J. Trump, though the popular vote went to his opponent, Hillary Clinton.

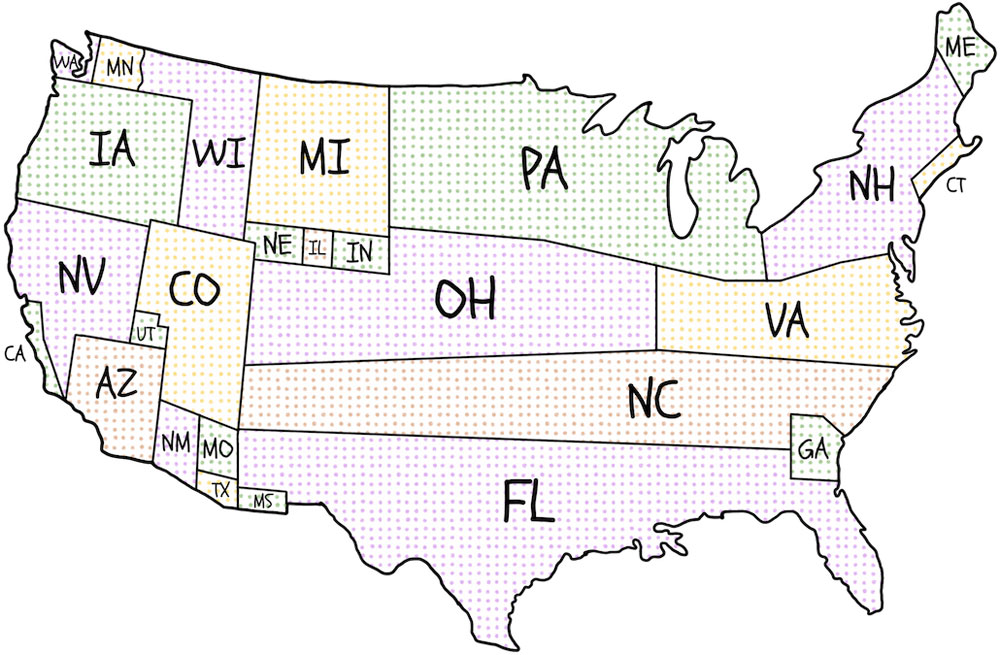

The winner-takes-all formula for delegates to the Electoral College means presidential candidates visit some states a lot and some not at all.

This is how the US map looks with state sizes based on the number of campaign events in 2016 (missing states had no campaign events). Presidential candidates are more motivated to address issues of concern to voters in swing states than in states where outcome is a foregone conclusion.

The National Popular Vote (NPV)

Court is among those who believe that increasing discrepancies between the electoral and the popular votes reveal the need for fundamental reform. Given the complexity and difficulty of amending the Constitution, she supports the National Popular Vote (NPV). With a measure to repeal Colorado’s participation in the NPV on Colorado’s November ballot, Court believes Colorado should retain its commitment to it.

The NPV will create a more democratic process, in which all votes for president count, says Court. Under the current winner-take-all system, all that matters is how the majority in a state votes—their electors are bound to go in that direction. “Fifty percent plus one in any given state and that’s the majority in that state. So, it doesn’t matter how many more than that fifty-percent-plus-one vote,” says Court. The NPV will “make every vote for the highest office more consequential.” Down-ballot votes are not impacted by the Electoral College, and would not be impacted by the NPV.

Several nonpartisan surveys including one by the Pew Research Center, suggest that a large proportion of US adults would like to amend the Constitution to eliminate the Electoral College. In the past decade, however, this has become an increasingly partisan issue, with about 2/3 of Republicans preferring to retain the institution (up from about 50% a decade ago).

The NPV is an interstate compact that keeps the Electoral College while fundamentally shifting the nature of future presidential elections by eliminating the winner-take-all approach to electoral votes, which has no basis in the Constitution. Proponents believe the shift would guarantee that all votes—rural and urban, large state and small state—carry equal weight. NPV opponents fear it undermines the founders’ vision of elections.

Colorado’s status as a battleground state ensures frequent campaign stops, as candidates compete for the state’s nine electoral votes. Many other states are treated as “fly-over country,” receiving little if any attention from presidential campaigners who treat the outcomes as foregone conclusions. NPV proponents hope it will encourage greater voter participation in both parties—GOP voters would be more likely to cast ballots in states that always go to the Democrats and vice versa.

Court explains the NPV as “a compact between the states that are saying, we will band together and agree we will tell our electors that they are to vote for the candidate who wins the national popular vote.” Once states with a total of 270 electors have passed the measure, they could then put this compact into practice. The NPV currently has just 196 electoral votes, so the outcome of the measure on Colorado’s ballot will not impact the 2020 election.

For more information, be sure to look for the Colorado Blue Book, a nonpartisan booklet prepared by the Legislative Council Staff that should appear in readers’ mailboxes beginning in late September, and will also be available at https://leg.colorado.gov/ The Congressional Research Service also updated its detailed consideration of both sides of the NPV in October 2019: https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R43823.pdf

This is confusing. You are talking about a yes vote to repeal it (a no vote being to support the NPV). But a YES vote SUPPORTS the measure.

You are correct, John. We were unable to get the actual ballot language before we went to press and the experts we spoke to suggested that the ballot language would reflect what the article states; instead, they chose a very different wording! We did post a correction via social media as soon as we learned what the actual ballot phrasing would be.