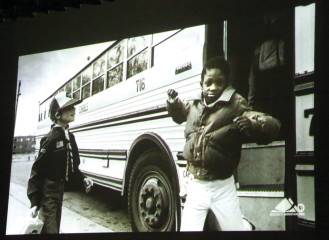

Participants at a Race & Equity Workshop are communicating for one minute with someone they don’t know about personal experiences that included a time they were at an advantage and a time they were at a disadvantage.

Community Conversations About Race

I’m amazed at the lack of concern, the lack of people knowing of this issue and caring enough to be here … I think until we get more people on board to understand that there is a problem, then racism will continue to be a problem. —Alicia Biggs, McAuliffe teacher

Terence Johnson, Chief of Schools at KIPP in Memphis, led a race and equity training event sponsored by Bill Roberts and McAuliffe schools on Jan. 12.

Comments from NE Denver community members who participated in discussions about race and equity on January 5 and 12 at McAuliffe School affirmed the importance and value of the conversations. Participants spoke candidly on subjects that get avoided in everyday life.

Comments from NE Denver community members who participated in discussions about race and equity on January 5 and 12 at McAuliffe School affirmed the importance and value of the conversations. Participants spoke candidly on subjects that get avoided in everyday life.

At a time when polls show 68 percent of Americans agree that “a big problem this country has is being politically correct1,” these community members were examining their feelings on a controversial subject, sharing them, and listening respectfully to differing opinions. Where being PC is about avoiding the real issue, these conversations were attempting to address the real issue.

“It is important to talk about race because the current dialogue in our community and country is so negative and loaded with judgment,” says Bill de la Cruz, the director for equity and inclusion at DPS. He says the subject is uncomfortable because we don’t want to be called a racist and we don’t want people to think we’re biased or judgmental. “In the white community, there’s this feeling people don’t really have to talk to their kids about the impact of race, but they’re going out into a multi racial world—and parents don’t know how to talk about that.” On the other hand, says de la Cruz, for some folks of color, the conversation is part of their lives to protect themselves and their children from potential harm of being discriminated against.

In 2013, twenty years after busing ended, former school board member Mary Seawell was concerned that Denver schools were resegregating—and she started thinking about a documentary on segregation and the achievement gap. “People have the hunger and desire to talk about this and they feel so paralyzed and powerless when they see things like Ferguson.

Community members view, then discuss a documentary about race and the achievement gap in DPS at McAuliffe on Jan. 5.

Brendan Weyi says when he was a child in DPS his father asked that he be tested for the gifted program and was told the program wasn’t traditionally for minority students. He finally took the test and got the highest score in the school’s history.

“We have these scripts in our heads about certain topics. I think we talk to people that agree with us all the time and see the world in the same way and we get kind of lazy,” said Seawell. “When you bring in something people care about, maybe they’re not as comfortable talking about it, their brain and their minds have to open up a little bit to find the right words. That’s a good thing for all of us.”

The four-part documentary, “Standing in the Gap2,” was shown in the four quadrants of the city. After viewing it, participants responded to questions. Stapleton resident Chris Adams facilitated the discussions using clickers that instantly showed the audience’s range of responses. The McAuliffe audience, which was 60 percent white, almost unanimously agreed (96 percent) that racial and ethnic segregation is a problem that needs to be addressed. Sixty-eight percent agreed that racism is an institutional issue more than an individual issue.

McAuliffe teacher Alicia Biggs says, “The problem with racism is that we’re too afraid to discuss it.”

In the discussion of institutional racism, one speaker said, “Racism is absolutely institutional but it is also individual. I think part of the problem is that we’re not owning our own racism. And that’s a horrible hard thing to say. I as an individual am responsible for my own racism.” Another speaker said, “I am personally not racist. But actually I do a lot of racist things just by virtue of being a white person in this society, unintentionally.”

Greg Cradick, a white dad with two adopted children of color, in a follow up conversation, said you can make the distinction between racial bias, which is unconscious, and racism, which is conscious. But, he added, “I think separating those out is dangerous because it kind of lets white people off the hook. The outcome is the same. You’re making a judgment of someone based on their skin color. To the person who feels they are being oppressed, it doesn’t matter whether it’s conscious or unconscious. It’s racist.”

A week after “Standing in the Gap,” Clarence Johnson, Chief of Schools at KIPP in Memphis, led a race and equity workshop, sponsored by Bill Roberts and McAuliffe middle schools. Participants discussed topics that revealed personal vulnerabilities to a person they didn’t know. Questions included: Describe a time when one of the elements of your identity appeared to hold you back? Talk about a time when you noticed inequity and you should have done something about it and you didn’t.

A participant commented during the workshop that the discussions with a stranger made him feel vulnerable. Erik Cohen, Bill Roberts vice principal, subsequently explained that one of the foundational elements of a relationship is shared vulnerability. “If talking about race makes people feel uncomfortable, they’re opening themselves up. It creates that shared vulnerability and a relationship can begin to form.”

DeRonn Turner attended the race and equity workshop and believes these workshops are very helpful and schools should have them for parents on an ongoing basis. And she is passionate about the need for culturally responsive teacher training in all DPS schools.

Both Cradick and de la Cruz raised the notion of color blindness. De la Cruz says, “People who are different want you to see who they are. Whether I’m disabled, whether I’m black, whether I’m brown, woman, gay, different religion. People want to be seen for who they are. The notion I don’t see you that way is a form of privilege that says I don’t need to have these conversations.” Cradick says he was brought up to believe “color blind is a great place to be,” but, in reality, it doesn’t exist for anybody.

A Conversation with DeRonn

We sit side by side on the couch in a living room that feels comfortably like the middle class home I grew up in—it has a big dining table for a family with four kids (like mine), and dad finishes the kitchen cleanup while mom chats. Polite kids occasionally pop through the room but they know the rules—no interrupting adult conversations. We have much in common—we both live in households with hard working, loving and stable families.

But one small difference between us—skin color—meant our lives unfolded in dramatically different ways. Racism was never even mentioned in my childhood. It has permeated her life.

DeRonn moved to Denver from Tulsa because of harassment after she filed a lawsuit against the city and the police department for police brutality. It took six years to settle.

She worries her teenaged sons, “bigger than your average bear,” will be followed in the grocery store just because they are black males—or put in jail.

She was heartbroken when her daughter came home from kindergarten and said some girls wouldn’t play with her because, “They said I was too dark.”

“You work just as hard as anyone else. You love your children just as much as anyone else. But being a black woman, it’s like we’re invisible. Really. People say, ‘You all are loud and you’re this and you’re that,’ but nobody hears what we’re saying. Oprah a few years ago gave an excellent example of racism. She said, it’s like if someone is physically hitting you and you keep saying it hurts and they say no it doesn’t. That’s what racism feels like.

“I sometimes imagine what it would be like for someone who is white to carry around that burden. It’s like this huge gorilla on your back all the time—a tremendous weight. Oh gosh. Let’s not let anything happen today.

“It makes me sad that people would fear another group of people so much that in their mind, even though on the surface they’re nice, in their heart they look at me as being less than human. That’s what it feels like.

“I’ve had people say get over it and move forward—but the memory and the heaviness of that doesn’t leave right away.

“Until some acknowledgment and recognition of the fact that these things exist happens, it’s going to keep perpetuating itself.

“Make eye contact, smile, say, ‘How are you doing today?’ Be genuine. It makes a difference in people’s lives. One word can change a person’s whole day. Even if they don’t look like you or aren’t in your income bracket. On the smallest level, just acknowledge people.

“Down south you see racism on a very visceral level. Sometimes I would rather it be very visceral and in my face than how it sometimes tends to be here. Here there’s this really kind of crazy undercurrent, like it’s just under the surface. We all know it’s there but nobody is trying to pop the balloon, they keep kind of letting it bubble up to the surface and pushing it back down. As soon as somebody pops it, it’s going to let out a whole beast of issues. That’s why instead of that happening, that’s another reason we have to have these conversations.”

DeRonn (Roni) Turner lives in NE Park Hill with her husband of 20 years, Vincent, and their four children aged 5 to 16.

1 Farleigh Dickinson University PublicMind poll. The poll of 1,026 adults across the country was conducted Oct. 1-5, 2015 and had a margin of error of plus or minus 3.7 percentage points.

2 “Standing in the Gap,” Rocky Mountain PBS Senior Executive Producer Julie Speer, sponsored by Gates Family Foundation, the Piton Foundation, Rose Community Foundation, David and Janet Mordecai Foundation.

0 Comments